“The original title of this play was Fungus!”

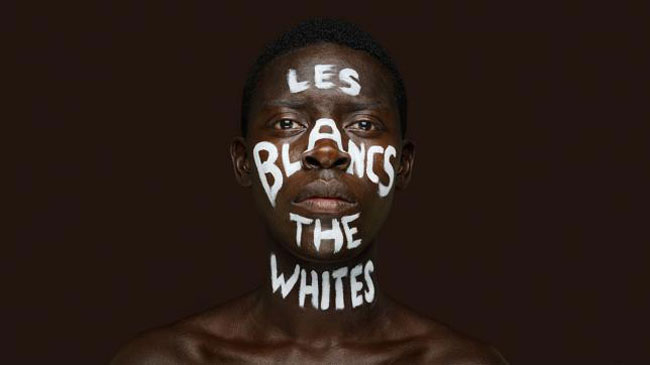

This is one of many lesser known facts about Lorraine Hansberry’s Les Blancs, which lie at the fingertips of Drew Lichtenberg. Though he works stateside, as the Literary Manager and Resident Dramaturg of the Shakespeare Theatre Company in Washington, DC, Lichtenberg worked as the dramaturg on the play’s recent London premiere at the National Theatre, more than 45 years after it was first staged on Broadway. “This is the play that Lorraine considered to be her most important work, if not her masterpiece,” Lichtenberg continues. “And there was this sense that it remains an important story, one that needs to be told again and again.” Lichtenberg was successful in bringing Hansberry’s work back to the forefront of the theatrical consciousness by colaborating with decorated South African director Yaël Farber, and Joi Gresham, the executive director of the Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust, literary steward of Hansberry’s estate, and the daughter of Robert Nemiroff, Hansberry’s former husband and literary executor.

Les Blancs could hardly be considered lost, Lichtenberg concedes, but it took a call from the National Theatre to Farber — and from Farber to Lichtenberg — to bring the work back to his attention. The two had met in the fall of 2015, while working together on Farber’s adaptation of Salomé for the Shakespeare Theatre, and Farber reached out to Lichtenberg for his thoughts on Les Blancs. He had no idea that he was auditioning in part to be her dramaturg.

“It took me a few weeks to get around to it, but eventually I assigned myself the play as homework, spent a weekend reading it and taking notes, and ended up emailing Yaël a few thousand words’ worth of thoughts and questions. Mostly questions. The play has always fascinated me, but the version available to most of us has always seemed like a text with as many gaps and dramaturgical leaps as answers. I must have said something that resonated, because Yaël reached out to the NT, and they began negotiating to bring me over to London.”

Before Lichtenberg joined the company in London, however, Farber introduced him to Gresham. Gresham, who holds copyrights and grants licenses for Hansberry’s works, was the first to extend an invitation to Farber to work on a restoration of Les Blancs after speaking with her about her initial vision of the play. Gresham’s hope was to revitalize the piece, drawing on Hansberry’s and Nemiroff’s early drafts of the play. This workshop experience has become a part of the larger LHLT Restoration Project that also includes The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, produced as a fiftieth anniversary revival at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2014.

To truly examine the play, Gresham arranged for Lichetenberg to visit the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the branch of the New York Public Library in Harlem where Hansberry’s papers reside. Arriving in Harlem, Lichtenberg realized that Les Blancs actually consists of three almost finished drafts of the play — each of them taking a radically different approach — as well as research clippings and notes. The play, a source of great passion and angst to Hansberry, remained unfinished at the time of her death from cancer in early 1965. In her final diary entry, poignantly, Hansberry expressed her desire for someone has to finish this play.

Four years later Robert Nemiroff, Hansberry’s creative collaborator, undertook the daunting task of compiling the drafts into a production text, acting in his capacity as her Literary Executor. This version of the play was then produced on Broadway, but Lichtenberg realized, while sitting in the Schomburg Center, that it was closer to a director’s cut, an unexpurgated text that reflected the three different drafts, at different points in the work’s development.

“I think what Nemiroff had done, because of his tremendous love for Lorraine and for her work, was that he came up with an episodic dramaturgy that allowed him to not cut anything.”

With his materials from the Schomburg Center, Lichtenberg met with Gresham met Farber in her Montreal home in February of 2016 to reexamine the bones of the play. Seeing the work, Gresham gave her blessing to Farber and Lichtenberg to shape the material in line with Hansberry’s wishes.

“Someone needed to go back and read the manuscripts and then have the go-ahead from the estate and really mold it so that it moved the way in which she originally wanted it to move.”

But what of the work itself?

The play, set in the mid-century era in which European colonies still exerted political power, centers on Tshembe, an African expatriate. Returning home from Europe to bury his father, Tshembe finds that his brothers have changed during his absence, as the gathering political strongholds in the nearby village force them to choose between radicalization and collusion with the white settlers. Tshembe, who seeks to remain a free man and rational decision maker, is pulled, inexorably and tragically, into the turmoil around him.

“The play is an entire society in microcosm while it’s also telling that story through a family drama… she synthesizes the macrocosm in the microcosm in a very powerful way.”

What surprised Lichtenberg the most about the play was the manner in which Hansberry was, while writing in the early ’60s, prophetically looking forward to the radicalism that would mark the end of that decade.

“Her era was the very early days of black nationalism, of Malcolm Little becoming Malcolm X, of Cassius Clay becoming Muhammad Ali, of LeRoi Jones becoming Amiri Baraka. Lorraine was friends with Nina Simone, and she was the one who radicalized Nina Simone, not vice versa. Nina Simone wrote “To Be Young, Gifted and Black” about Lorraine Hansberry.”

According to Lichtenberg, Hansberry should be remembered as much for Les Blancs as for A Raisin in the Sun, her first play, which became the first ever produced on Broadway that was written by an African-American female.

“She really thought of Raisin in the Sun as almost an apprentice piece. I think she was bothered by the manner in which its vision was domesticated, turned into uplift. Raisin individualizes these issues down to a family, which is potentially very powerful, but Les Blancs refuses to work on that scale. It has a tragic grandeur that is self-consciously classical.”

If Raisin was uplifting and domestic, Les Blancs is explosive and epic.

“She was ahead of her time in a pretty profound way. This play in many ways predicts the schism that would happen in the civil rights movement between violence and non-violence. It also forecasts what would happen in Algeria, in South Africa, in all of these countries where wars of ind

ependence would be fought.”

It comes as no surprise as why this would be the perfect play to be produced in 2016. In light of recent social events and the creation of the #blacklivesmatter movement, the National Theatre was onto something in programming this gripping work by Hansberry.

“It has a lot to say about #blacklivesmatter and about the lack of progress since the era when Hansberry was writing. It brings a historical consciousness to bear. You know, this is a play about a subject—African colonialism — that had not been dramatized before…. It’s saying that there was this great injustice that was done and that it will keep on producing violence until we acknowledge it.”

The production received rave reviews from several London news outlets (check them out here, here, and here) and was extended. But beyond critical acclaim, the work finally received the staging it deserved. By treating Hansberry as one of the most powerful writers of the 20th century—by giving them the freedom to work with her materials in a manner that liberated her inner vision—Gresham allowed Farber and Lichtenberg to make Les Blancs speak with an unmistakably contemporary voice. Scraping away decades of dust, they found a story that warrants being retold, again and again.

“This is the essence of Lorraine Hansberry’s project, isn’t it?” Lichtenberg says now, his voice rising with excitement. “That there is just this open wound, this fungus, this festering wound that has not healed and will never heal until we can tell the story and bear witness.” He smiles. “But Les Blancs is a better title.”

Inspired by True Events: A Conversation with Playwright Ryan Spahn

Plays About Technology