Dorian: They say that when good Americans die they go to Paris.

Lady Agatha: Really? And where do bad Americans go when they die?

Lord Henry: They go to America.

That pithy exchange is from the new adaptation of The Picture of Dorian Gray I had the pleasure of adapting with Oscar Wilde’s grandson, Merlin Holland. It is one of many references to America and Americans in Wilde’s only novel, and there are countless more in his short stories, essays, and plays. While Wilde was always happy to use America as the butt of his elegant jokes, he actually had a deep affection for the country, because it was in America that he made his name and began to write for the theatre.

It may surprise you to know that the first production of an Oscar Wilde play did not take place in London or Dublin or Paris, but in New York. The play was called Vera; or, The Nihilists and was produced at the Union Square Theatre on August 20, 1883. The twenty-eight-year-old author was at the opening night, but despite a great deal of hullabaloo, the production closed after just one week. The New York Herald review called it “long-drawn dramatic rot.”

This was a full nine years before the run of society comedies that secured Wilde’s reputation as a playwright, beginning with Lady Windermere’s Fan in 1892 and culminating with The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895.

We tend to think of Wilde as always having been a literary genius, but he didn’t, in fact, become a successful playwright until he was in his late thirties. So what was he doing in America ten years before, and how did he come to make his theatrical debut there? To answer that, we need to take a step back in time.

After coming down from Oxford University in 1878, Wilde settled in London and became associated with the Aesthetic Movement — the philosophy of “Art for Art’s Sake” espoused by John Ruskin, Walter Pater, and William Morris, amongst others. He befriended painters, like the expatriate American James McNeill Whistler; society beauties, like Lillie Langtry; famous actresses, like Sarah Bernhardt; and made sure he was seen at all the right parties and openings nights.

The great Polish actress Helena Modjeska arrived in London in 1880 to perform a season at the Court Theatre. She remarked of Wilde: “What has he done, this young man that one meets him everywhere? Oh yes he talks well, but what has he done? He has written nothing, he does not sing or paint or act — he does nothing but talk. I do not understand.”

One hundred thirty years before the Kardashians, Wilde was quick to realize that you did not have to do anything to become famous; it was simply enough to be and to get noticed. And noticed he was. Frequently satirised in the press and in magazines as a sort of limp aesthete, he was often depicted surrounded by sunflowers or lilies, or in the case of this cartoon in Punch, as one himself.

Far from doing him any harm, this type of attention simply proved Phineas T. Barnum’s maxim that “there is no such thing as bad publicity.”

When Gilbert and Sullivan sought to satirise the Aesthetic Movement in the operetta Patience, they used Wilde as one of the models for the poet Bunthorne. Wilde attended the first night and is said to have remarked: “Caricature is the homage that mediocrity pays to genius.”

The operetta proved highly successful, and it wasn’t long before it was invited to America. However, the Aesthetic Movement was unknown stateside, so the producers were worried that the audience would not be in on the joke. So, they hit upon an ingenious plan: Why not invite a real Aesthete over to America to give a lecture on art or dress so that the audience could see for themselves who was being ridiculed? It wasn’t long before Wilde received a telegram from D’Oyly Carte’s office in New York: “Responsible agent asks me to inquire if you will consider offer he makes for fifty readings beginning November first.” Wilde replied: “Yes, if offer is good.”

And so it was that on January 2, 1882, Oscar Wilde arrived in New York on the S.S. Arizona.

A team of reporters was there to greet him, and he made the most of the opportunity by providing memorable quotes. When asked how he had enjoyed the voyage, he answered that “the Atlantic Ocean has been a great disappointment.” When going through customs legend has it that he told the inspector “I have nothing to declare but my genius.”

Wilde was due to tour America for a number of weeks but ended up staying a year. He was invited as an object of ridicule, but his genius for self-promotion led to his becoming a celebrated figure, touring over one hundred forty towns and cities — everywhere from Montreal to Memphis, Sacramento to St. Louis. He lectured mainly on art, interior design, and dress. His image was used (illegally) to advertise everything from cigarettes, to corn, to Madame Fontaine’s Bosom Beautifier: “Just as sure as the sun will rise tomorrow…so sure will it enlarge and beautify the bosom.”

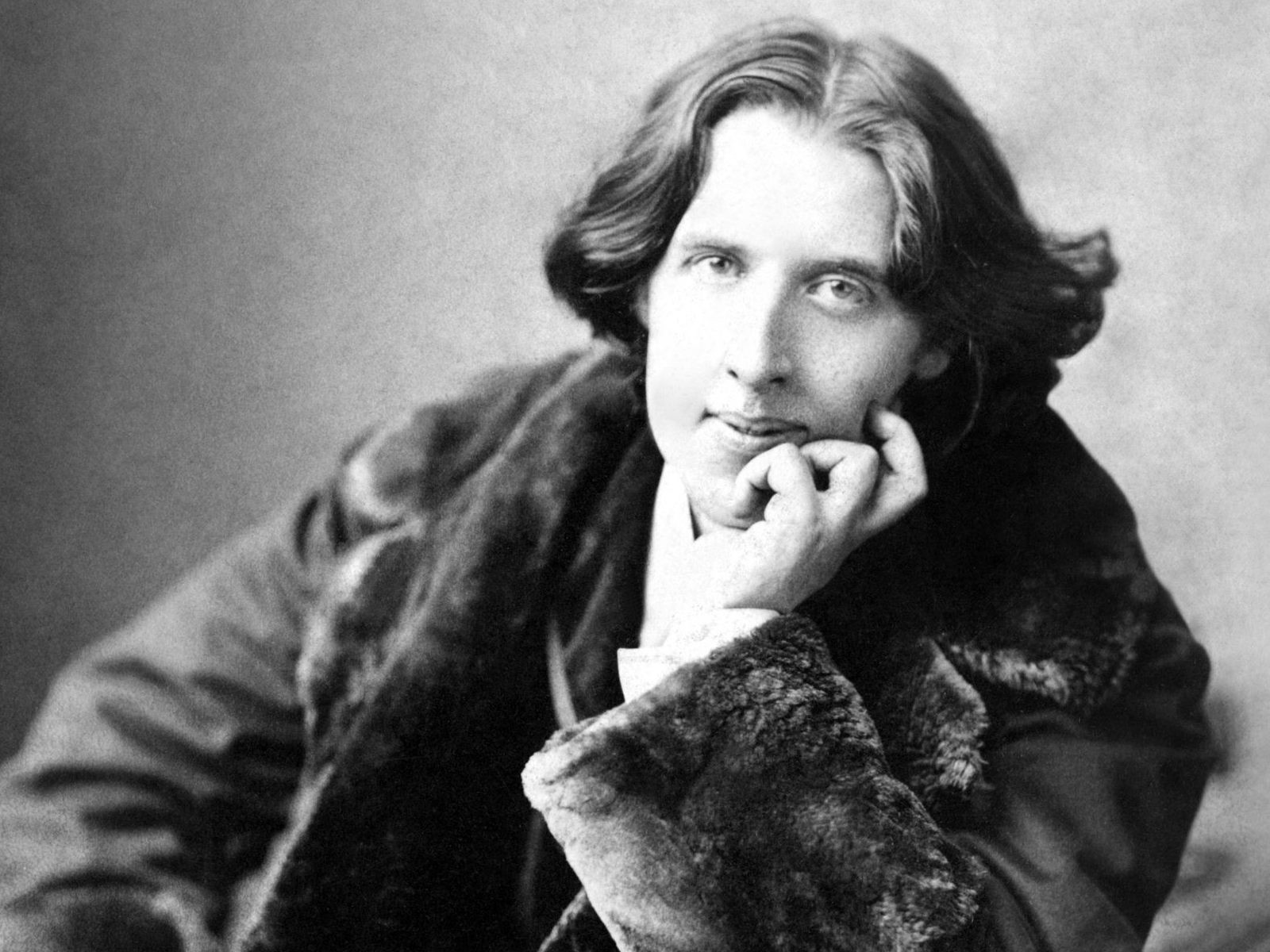

The most iconic images of Wilde we have today (like this one) were actually taken in New York at the studio of Napoleon Sarony at 37 Union Square. It was in America that Wilde perfected his image, and it’s ironic that this image was the subject of a lawsuit that changed US copyright law forever. Sarony successfully sued a company that had reproduced 85,000 copies of this picture of Wilde, claiming ownership over the copyright of a photograph for the first time in legal history. Even this early in his career, Wilde was the subject of a legal controversy with far-reaching repercussions. A decade later, he himself instigated another legal action (as documented in our play The Trials of Oscar Wilde), but with devastating personal consequences.

During his travels, Wilde was introduced to the literary giants of the day — Walt Whitman, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Louisa May Alcott, and Henry James. He met former President Ulysses S. Grant and spent the night at former Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ house in Mississippi, a meeting that didn’t go so well. “I did not like the man,” said Davis, which shows that even then Oscar had the talent to violently divide opinion.

Wilde lectured in Saint Joseph, Missouri two weeks after Jesse James had been murdered there and found the whole town in mourning. “Americans are certainly great hero-worshippers, and always take their heroes from the criminal classes,” he observed. In Leadville, Colorado he was winched down into the depths of a silver mine and delivered a lecture to the miners on the ethics of art. “I read them passages from the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini and they seemed much delighted,” he said. “I was reproved by my hearers for not having brought him with me. I explained that he had been dead for some little time which elicited the enquiry, ‘Who shot him?’ They afterwards took m

e to a dancing saloon where I saw the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across. Over the piano was printed a notice: PLEASE DO NOT SHOOT THE PIANIST. HE IS DOING HIS BEST.”

Wilde was unimpressed by America’s greatest natural wonder: “Niagara Falls seemed to me to be simply a vast, unnecessary amount of water going the wrong way and then falling over unnecessary rocks.” However, he greatly enjoyed California, which struck him as “very Italy, without its art.” In San Francisco, he was given a tour of the Chinese quarter, which he described as “the most artistic town I have ever come across.”

In Lincoln, Nebraska he was shown around the prison. “Little whitewashed cells so tragically tidy, but with books in them,” he wrote. “In one I found a translation of Dante. Strange and beautiful it seemed to me that the sorrow of a single Florentine exile should, hundreds of years afterwards, lighten the sorrow of some common prisoner in a modern gaol.” Perhaps this stayed with him, for Dante’s The Divine Comedy was one of the few books Wilde was allowed to read when he was a prisoner himself fifteen years later.

“America is not a country, but a world,” Wilde said admiringly. It was a world that welcomed him and gave him an audience, that allowed him to develop his nascent thoughts on art, that gave him the opportunity to travel and live off his considerable wits, and that took him seriously and produced his first play. Perhaps most importantly, this new world paid him a small fortune and gave him the freedom to pursue a career as a writer. For that, the rest of the world should be eternally grateful.

Oscar Wilde may have visited your town, city or local theater. You can see the schedule of Oscar Wilde’s 1882 tour of America here.

The Trials of Oscar Wilde and The Picture of Dorian Gray by Merlin Holland and John O’Connor are both published by Samuel French.

MERLIN HOLLAND

Merlin Holland is a biographer and editor and is the only grandchild of Oscar Wilde. For the last 30 years, he has studied and researched Wilde′s life. He is the co‐editor, with Rupert Hart-Davis, of THE COMPLETE LETTERS OF OSCAR WILDE, and the editor of IRISH PEACOCK AND SCARLET MARQUESS, the first uncensored version of his grandfather’s 1895 libel trial. He has also written THE WILDE ALBUM, a small volume that included hitherto unpublished photographs of Wilde. In 2006, his book OSCAR WILDE: A LIFE IN LETTERS was published, and COFFEE WITH OSCAR WILDE, an imagined conversation with Oscar, was released in the autumn of 2007. Holland also wrote A PORTRAIT OF OSCAR WILDE (2008), which reveals Wilde through manuscripts and letters from the Lucia Moreira Salles collection, located at the The Morgan Library & Museum in New York City.

UK School Musicals – Let’s Travel

The Devil’s in the Details: Sharp Satire, Native Gardens and an Interview with Karen Zacarías