Monica Dolan is an award-winning actor and writer, with performance credits including W1A, Appropriate Adult, Witness For The Prosecution and Strike: The Silkworm. She starred in her debut one-woman play, The B*easts, at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2017 and the role won her The Stage Edinburgh Award for Outstanding Performance. The B*easts transferred to The Bush Theatre in Spring 2018. Here, Monica discusses the inspiration for writing the play and her experiences of performing it.

Tell us about what inspired you to write The B*easts?

I had been writing another play (which is still in my bottom drawer) that explores many of the same themes in The B*easts, and much of the research that went into that play found its way into this one. I had been thinking about these topics for some time and they were obviously ideas that I was interested in and cared about, but I think that to make a play, there has to be some specific trigger to focus them. You never know when your subconscious is going to tap you on the shoulder with a play. I was at a spa weekend with my friend after a long job and we were on sun-loungers, relaxing at one end of the swimming pool. Lots of those spa places have funny sort of pseudo-Roman and Greek statues, or bits of statues, dotted around, and at the far end of the pool was a torso-upwards female figure of very slight, childish build, but of womanly attributes. That visual trigger gave me the idea for the story.

You mention in your introductory note to the playtext that one of the first responses to your performance was, ‘is this based on a real story?’ Was that a surprise?

It was a great surprise at the time that anyone might think that this is a true story, but I suppose that part of whatever power lies in the tale is that we are not 100% sure it could not be true, and we can follow how this might happen. If we saw the story on the cover of a tabloid, we might be shocked, but perhaps not surprised. It might be the logical next step. Certainly since having the idea for the story, which was very much conceived as a “what if?”, I have discovered that a great many of the elements for it to come about do exist. Makeover apps and even plastic surgery apps (which are basically plastic surgery simulators) are targeted at girls as young as nine, the umbrella term of “cosmetic procedure” is wide, and age regulations for cosmetic procedures seem to cover tattoos and tanning but not much else. Role models for children have changed dramatically; whereas in times gone by, a role model for a young girl might be her sister, her mum or a girl in her street, there is now a glut of advertising and internet imagery to pool from – much of it selling perfection.

What’s the story behind the “*” in the title?

I am not entirely sure! What has been interesting to me is how people are interpreting it. A young woman working in theatre administration came up to see me the other day and said that she liked the asterisk in the title because it was making a comment on breasts and censorship, but I do not know if that was what I had intended. I like the fact that it is a pun and that the asterisk creates the word “beasts”, which applies to other aspects of the play. I enjoyed the mischief of it; I grew up with plays like Shopping and F***ing, which had to have asterisks in the title at the time for censorship and obscenity reasons, but in fact the asterisks really draw more attention to the word itself, and actually perhaps seem a little quaint to us now.

I suppose that the asterisk in The B*easts delivers a coyness, which has a little challenge in it somewhere, and hopefully a sense of intrigue. Therein is certainly a wink and a fondness for the plays that were growing at the time that I was growing up in the theatre, and which have arguably become the established plays that emerging works now both build upon and react to.

The B*easts directly confronts the pornification of our culture and the sexualisation of our children. Why do you think that the monologue form is such an effective way to discuss this topic?

I think it is useful for what it can leave out. For this particular subject, a useful thing that the monologue form avoids is any direct images of a child or children. However evocative a description of a circumstance or a person, the monologue cannot take the audience’s mind beyond the jigsaw of images that it already has to hand, and so in that sense I feel that, although there are aspects of the play that might be shocking or uncomfortable, there is little I can do that might actually corrupt the audience. The monologue form encourages the audience to feel, and most definitely to think, as at any moment they will be challenging, agreeing with or identifying with the character in their own heads.

I have seen plays that have shown images or incidents that have actually made me feel ill, and whatever point the playwright was trying to make has been overridden by the way in which they have made it. This particular topic is very emotive, and the monologue form is helpful in that it can perhaps help us see the subject more objectively, which ultimately might prove more helpful in doing something about it.

I have found it very freeing to write in this form as it lends itself so happily to storytelling. Although so much of the play deals with modern phenomena like targeted advertising, the fact that the main character is a conduit for a story means that there is a slight fairytale or fable quality to it, which helps us to recognise that we are being asked to look at something from a timeless, moral perspective. In some ways, I feel I have more control with the audience too – though they might disagree!

This is your first published work. What were the challenges in moving from acting to writing? What’s it like to perform your own work?

Writing is much more solitary. I am a naturally collaborative creature – and the collaboration aspect does come later – but at first it is just you and your idea and your discipline and independence. There is no map like there is with acting, because you are the one drawing it. The possibilities are infinite.

There is a sort of a peace that comes with it though, and I would certainly like to do it more. It is quite odd performing my own work. In some ways, the ‘actor me’ is not always as solicitous about being as specific and accurate with the lines as I might be with another writer, and perhaps I have been a little less reverential to the writing – though I am strongly fighting this, and going through the lines every day, and when I ask others to test me, I make sure that they stop me if I get the tiniest thing wrong. It seems to have always felt like a slightly moveable feast, perhaps because we have been cutting in rehearsals. I have really come to respect the fact that whatever word I chose in the writing, I chose for a reason, and that whatever word I might lazily substitute in the moment may mean roughly the same but is not the right one, and is not as fitting rhythmically.

It is much more vulnerable to be performing my own work, which is both a good and a bad thing. If it goes badly, there is no-one else to blame, but if it goes well and provokes debate then I can afford to feel proud. It takes more confidence and bravery to perform it because I am delivering something that came from me, and that I care about it very deeply. It is more difficult to approach it objectively, and was more difficult to take it as seriously at the beginning as I might do with someone else’s work. I suppose it comes down to learning to respect my skills as a writer.

Why did you decide to tell this story from the psychologist’s perspective?

Tessa is a psychotherapist, which means that she has experience, she has other patients, and she has a unique perspective in that she is used to dealing with the world and troubled people in the world. She has the language to talk about sex and mental health freely and with authority, and all of the subjects in the play are well within her comfort zone as a doctor, though not necessarily as a person. We are

so funny about doctors: we tend to think that they can solve everything, but they are just people, and there is still so much out there in scientific and medical terms that they do not know and cannot help us with. I wanted to have a look at the resilience of health professionals and what they are confronting, and how that is changing. It has been pointed out to me by a psychotherapist who I know and some I have seen on documentaries.

The gift in exploring this particular subject from the psychotherapist’s point of view is that, although she is invested, she has a slightly “once removed” quality that means she can examine the sexualisation of the child in the context of the world and how the mother, the child, the world of the media and advertising, and the society feed each other in this respect. She can see the whole picture, and as a psychotherapist she has some of the skills to lead us through it and help us analyse it, but they do have a limit. Her being a doctor also means that, although she might want to give an opinion and we may guess her opinion, she is not at liberty to express a direct opinion. There is an interesting tension in this and we are led in an informed way, but ultimately invited to think for ourselves.

What would be the main challenges for anyone looking to stage a production of The B*easts?

The main challenges are learning it, and also very much keeping Tessa a human being, making sure that the thoughts come from her as a person as well as a doctor. Technically, the show is fairly simple, as there are not many cues: one lighting state and a few phone rings, and there does not have to be much movement. It is essentially a storytelling piece.

Describe The B*easts in five words.

Tale of sexualisation of culture.

To purchase the script for The B*easts, click here. The title is not currently available for licensing however you can register your interest in advance here.

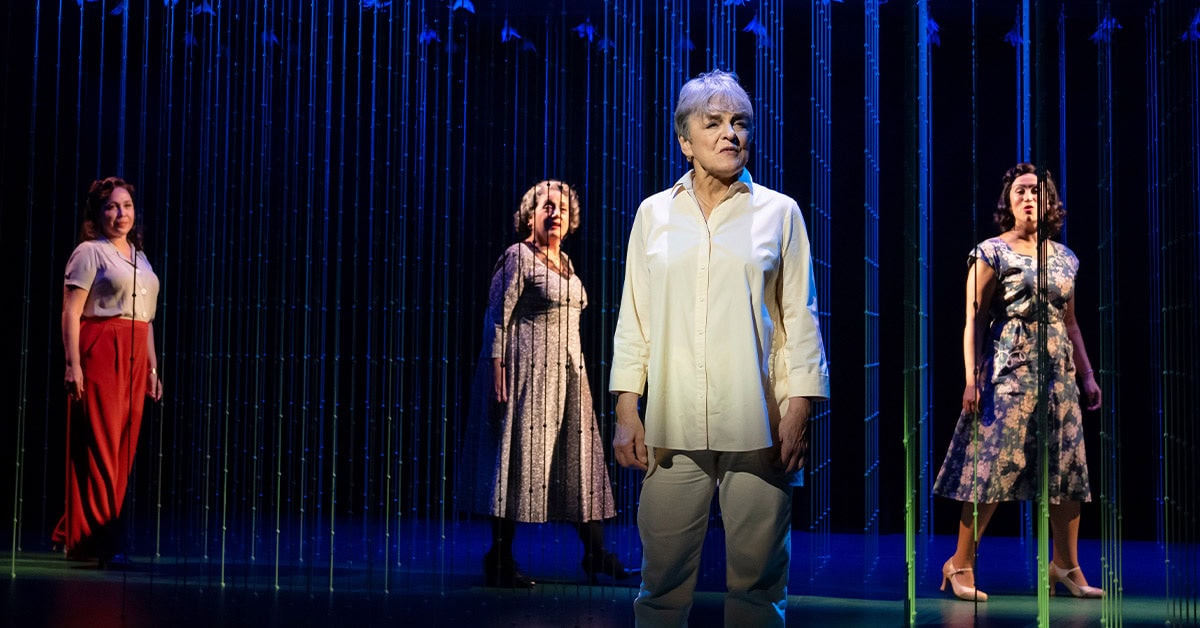

Photo credit: Alan Harris.

Unlikely Friendships in Musicals

Women Across Generations: Shows Featuring Female Characters of All Ages