Esther Freud trained as an actor before writing her first novel, Hideous Kinky, which marked the start of a hugely successful career as a novelist. Stitchers, Esther’s first play, debuted at the Jermyn Street Theatre in 2018 and follows the story of a remarkable woman and her mission to improve the lives of prisoners through needlecraft classes. Here, Esther discusses the inspiration behind the piece, why the story of Stitchers was best suited to the dramatic form, and portrayals of prisons on stage.

…

Stitchers is based on the true story of Lady Anne Tree, who taught prison inmates how to use needlecraft as a way to build their self-esteem and confidence. What was it about this story that inspired you to write a play?

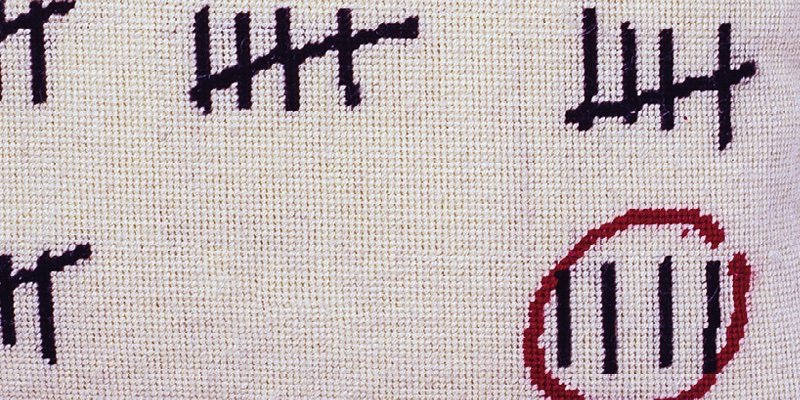

For a long time I’d been wanting to write a play, and I’d been hoping, waiting for a subject. Unlike a novel, where it’s possible to start with a place, a character, one conversation, I felt that I needed to know what my play was about before I began. Then one day the idea for Stitchers arrived. Male prisoners, learning to embroider. The subject had pathos and humour. I’d known about Lady Anne Tree’s charity, Fine Cell Work, since its inception, but had no idea how or why she’d become so passionately involved in prisoners lives. But I had seen the high quality of the embroidery the men produced, and I was aware of the stultifying boredom in which inmates often served their sentences. I wanted to tell Lady Anne Tree’s story, and also to tell theirs.

Beyond Stitchers, you’re well-known for writing novels (particularly the hilarious hit novel, Hideous Kinky). What’s the difference in writing prose compared to writing for the stage? And why, for you, did Stitchers have to be a play?

Ideas come to me in forms. A novel (mostly,) sometimes a short story. When Stitchers arrived it was a play. There was no other way to tell it. I started much as I would a novel. I did some research, prevaricated, and then jumped in and wrote a scene. Between bouts of research, I kept writing until I had a draft, re-wrote and re-wrote until the characters came to life, and the plot began to tighten. It was more technical than writing a novel, and I loved that I could read the whole draft in a day. I did imagine I would be able to write it more quickly, but it took a long time to get right. The more I discovered, the more responsible I felt for truthfully telling my characters’ stories. I visited a high security London jail every week for more than a year, making notes, talking to the men who attended a regular sewing group, until eventually almost every line spoken by a prisoner in the play was taken from life.

The play could be viewed as a social commentary on incarceration and its long-term impact on the mental wellbeing of inmates. What did you want audiences to take away from seeing the show?

Prison is often depicted as a place of violence and turmoil, but it is the loneliness and boredom, the twenty-three hour lock-up, that puts inmates in most mental and physical danger. I spoke to several ex-prisoners who told me how being given the chance to learn a skill, to create something of value, to be paid for it, was what got them through their sentence. More than one said that stitching had saved his life. And if you’re wondering why I concentrated on male prisoners, it is because most prisoners are men. 94%. Lady Anne Tree was a prison visitor for many years and understood how desperately those convicted of a crime needed a helping hand, to get through their sentence, to find work on their release. Everyone deserves a second chance, she said.

How do you strike the balance between the fact-based elements of the story and the more theatrical details needed to bring it to life on stage?

I was excited by the theatrical possibilities. How we might show the beauty of the stitching. Could we use lights, project images? It all depended on the theatre. Maybe we’d rely on words? One man told me how he hung the skeins of wool round his cell so he could see the colours. Others about their dreams and how they stitched them into the squares of the quilt. I hope that the bare facts of prison life can give rise to other more experimental ways of portraying the experience. I once saw a production of War and Peace performed by Gifford’s Circus where a character spins up to the ceiling in a dream. The possibilities are endless, and free to interpretation.

What advice would you offer to companies looking to stage Stitchers in future?

I think that this play, although I am passionate about its message, is about people, and so I’d hope the focus would be on characters that are believable, three dimensional, that we can connect with. Gaby Delal, my director added an inspired aspect to the play, with use of sound effects as the characters learnt to sew, and the set designer, Liz Cooke, created a set that was both versatile and arresting. Sound in prison is a major factor. The silence. The bursts of clanging doors. The outbursts, the running feet. On another most practical level, it must be taken into account how hard it is to sew, let alone thread a needle, while learning lines.

Before turning to writing, you originally trained as an actor. Do you feel that your experience of being a performer has influenced how you write for the stage?

Working as an actor is a useful experience for most things in life. I think it has influenced the way I write, generally, in every form. I’ve always been drawn to dialogue and found, early, reading so many plays had given me a sense of the structure and flow of a scene. I was grateful for it while writing Stitchers, but also grateful to be the author, at the back of the room during rehearsals, and even more grateful, on the first night when the responsibility shifted and the play was in the actors hands.

Learn more about licensing Stitchers (UK) and buy the script.

Newly Available for Licensing – January 2026 (UK)

Newly Available for Licensing – January 2026 (US)