By David Morris

Author & Editor of CollectingChristie.com

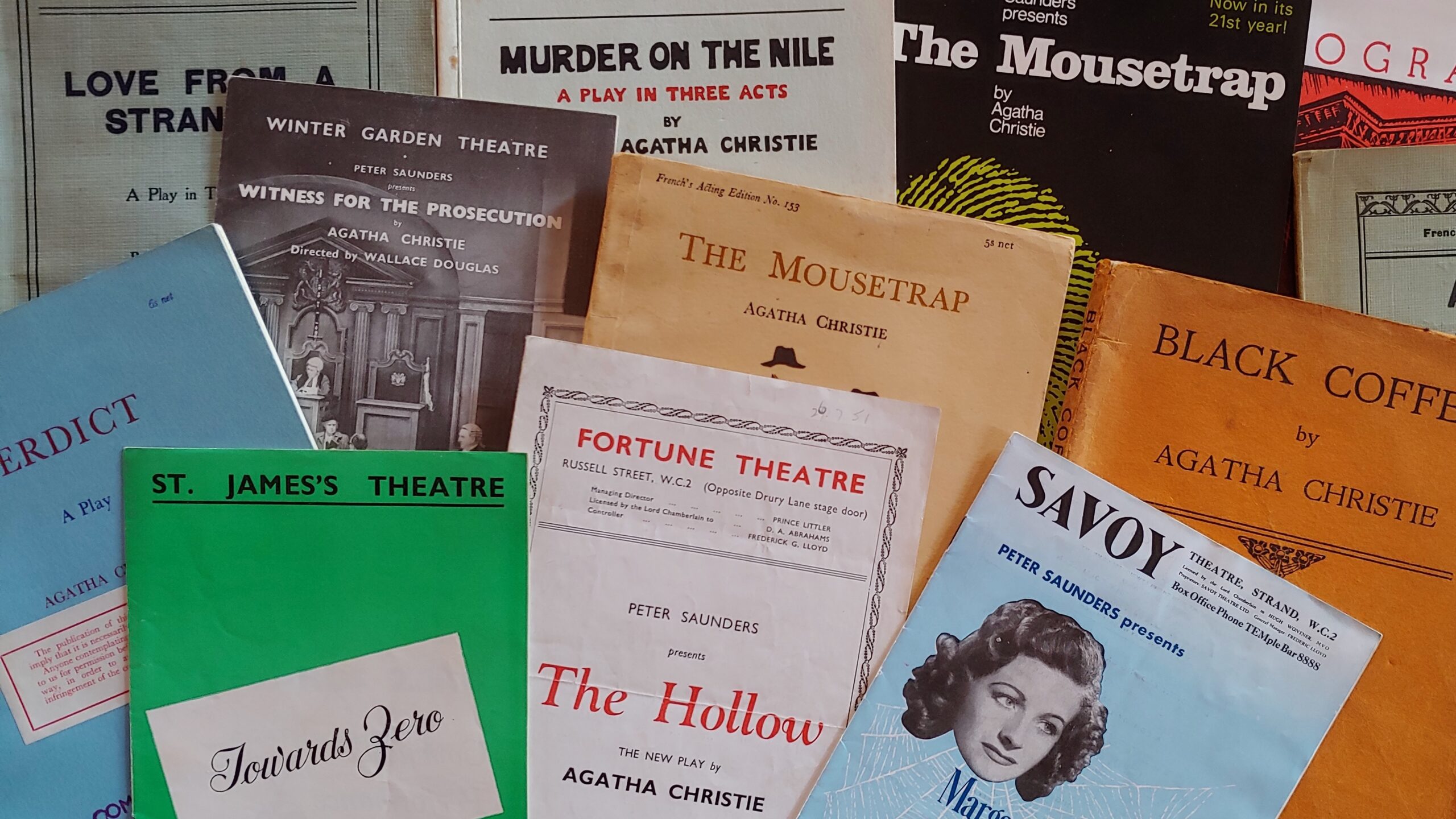

Agatha Christie is widely recognized as the most successful fiction writer of all time, as she has sold over 2 billion books worldwide. But she is also one of the world’s most successful female playwrights. She is known to have written 20 original plays – of which ten have been published. She also adapted 13 of her stories into plays. So, collectively, Christie penned 33 plays – many of which are now household names.

Christie clearly enjoyed writing plays:

“I find that writing plays is much more fun than writing books. For one thing you need not worry about those long descriptions of places and people. And you must write quickly if only to keep the mood while it lasts, and to keep the dialogue flowing naturally.” – Agatha Christie, c.1950s

As a collector of Christie-related items, in addition to collecting playscripts, I also collect theatre memorabilia. Between them, they can transport you back in time to the moment when these plays were new – from how they were promoted and who starred in them.

As we explore the world of Christie on stage, we’ll go chronologically – not based on the date the plays were written, but when they were first performed.

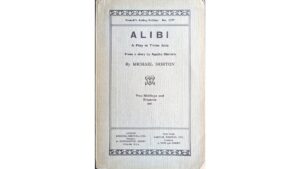

1928, May 15: Alibi (adapted by Michael Morton)

The first Agatha Christie story to be performed on stage was Alibi – adapted by Michael Morton and based on The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. It opened at the Prince of Wales Theatre in London on May 15, 1928. While the play’s script was generally not immediately published for people to buy, most of the time they were published within a few years of the play’s initial performances. The play featured Charles Laughton in the role of Poirot and was directed by Gerald du Maurier – Daphne du Maurier’s father.

Many of the vintage playscripts contained photos of the set designs. When Samuel French first published the playscript in 1929, it contained photographs of these original sets which really helps bring the play to life. There are two photos – one showing Roger Ackroyd’s home and the second showing what is likely the first ever representation of Poirot’s study on stage or screen.

It is also rewarding to read the props lists and staging cues in the rear of the playscripts. While it’s highly likely Christie didn’t write these, there’s a certain period charm to seeing the deemed importance of a Tatler or a Sketch magazine, as well as guidance on how to handle the stabbing of Roger Ackroyd!

Alibi also went to New York in 1932 – but under the slightly different title, The Fatal Alibi. It opened at the Booth Theatre on Broadway – a theatre named for the actor Edwin Booth, whose brother, James Booth, also an actor, infamously assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Charles Laughton, who starred in the role of Poirot in London, also transferred with the play to Broadway.

Numerous other Christie stories were adapted by other playwrights for the stage, but we’ll focus on the plays Christie wrote or adapted herself.

1930, December 8: Black Coffee (original)

In December 1930, Christie’s first original play appeared on stage – produced by the wonderfully named Mr. Whatmore. Originally titled After Dinner, Black Coffee premiered over a two-week run at the Embassy Theatre in Swiss Cottage – just north of Regent’s Park in London. Unlike almost every other play, the first printing of this playscript was by Alfred Ashley & Son, though later editions were printed by Samuel French. This original playscript is quite rare, and sadly lacks any photographs of the original set design.

The Samuel French edition published in 1952 features a depiction of Poirot on its cover, because – of note – this was the only original Christie play featuring her Belgian detective. In the four Poirot novels that Christie later adapted for the stage, she removed him from the story. So if you want to see a play written by Christie featuring Poirot, it has to be Black Coffee.

After Black Coffee, it would be 13 years until any fresh Christie-penned play was performed – and this was a play she adapted from her one of her books. It would be over 20 years after Black Coffee until another truly original Christie play appeared on stage.

1943, September 20: And Then There Were None (adapted by Christie)

The first of these reached the stage in 1943 – it was only the second Christie-penned play. In the UK, And Then There was None was performed with the same title as her 1939 novel, from which the play was adapted. Samuel French first published this playscript in June 1944.

While the play originally opened in Wimbledon, its West End premiere was at the St. James’s Theatre, where it stayed for its entire run – with the exception of about 8 weeks. On February 23, 1944, during what was known as the mini-blitz, multiple bombs fell in the vicinity of the St. James’s Theatre – with one landing on it. Luckily for theatregoers the bombs landed at 11:50pm, and during the war, theatre times were moved earlier to assist with blackouts. That evening, the play’s performance had begun at 5:40pm. As one says, the play must go on… and so it did at the nearby Cambridge Theatre until St. James’s could be reopened.

While many of the Samuel French playscripts were printed for the global market, a north American printing was done given the name change of the title in the US to Ten Little Indians – but now more correctly referred to as And Then There Were None. Rather shockingly, this early printing had a spoiler-filled synopsis of the play right in the front of the playscript and a rather unique description of the play as “a phantasmagoria of gruesome (though rather comical) details.”

It is generally believed that Albert de Courville, the British theatrical director, modified the script to make it more comedic. However, no working copy of his script has yet surfaced. It was promoted on posters in New York as a “hilarious mystery thriller” – so some questionable changes must have occurred.

The play’s New York Broadway run began in June 1944 at the Broadhurst Theatre. The play transferred to the Plymouth Theatre in early 1945 and finished its Broadway run here, lasting just over one year in total.

For collectors, finding any programmes for plays produced during World War II and through to the early 1950s is very challenging due to the paper rationing and recycling drives – this is true both in the US and UK. Programmes often included a notice of the requirement to share, and many were likely returned for reuse.

As with many of her plays, Christie made substantial changes to the novel – for And Then There Were None, she provided a different ending. Perhaps this is understandable with this play for a variety of reasons. Many theatregoers likely wanted a distraction from the ever-present reality of World War II, and the novel’s ending is certainly darker than the revised ending in the play. When one considers that this play was also shown to members of the armed forces – both at home and in the theatre of operations – the ending was likely far more appealing to them.

1944, January 17: Hidden Horizon / Murder on the Nile (adapted by Christie)

The next Christie play to hit the stage was her adaptation of Death on the Nile – originally billed as Hidden Horizon and then later as Murder on the Nile. It was first staged at the Dundee Repertory Theatre in January 1944. This play ended up in Dundee for its initial performance because of the actor Frances Sullivan. He credited that play’s director Mr. Whatmore as giving him his break back in 1930 – 14 years earlier – when he starred in Christie’s Black Coffee. Mr. Whatmore was now running the Dundee Repertory Theatre, and Francis Sullivan wanted to thank him by bringing a future West End play to him.

The first playscripts included a photo of the original set design. Perhaps less well known is that it was designed by Danae Sullivan – the wife of its lead actor Francis Sullivan.

The play toured various theatres in the UK before finally making it to the Ambassador’s Theatre in the West End in March 1946 – but it only lasted six weeks. In the US it opened in September 1946 but retained the original title Hidden Horizon – it only lasted 12 performances. Consequently, programmes from either the UK or US productions are exceptionally scarce. The US playbill from then tells us that it was produced and directed by the same team behind Ten Little Indians – the Shubert brothers and Albert de Courville.

1945, January 29: Appointment with Death (adapted by Christie)

Appointment with Death was adapted into a play by Christie in 1944. When she adapted the story, she significantly reworked it – including the motive and the whodunnit. In my opinion, the play offers a far more satisfying outcome for the reader than the novel and is one of my favourites, not only for the plot development, but also the dialogue and witty banter. If you enjoyed reading the novel, you must try reading this play. I think you’ll prefer the rewritten script too.

It opened in Glasgow in January 1945 and then went on a short national tour to Northampton and Manchester, before landing at the Piccadilly Theatre in the West End in March 1945. Surprisingly, this was another play that didn’t have legs – closing after 42 performances – making original programmes exceptionally difficult to find. Why it closed so quickly is open for debate, but these were the waning days of WWII in Europe – with VE day just a few days after the play closed – so people certainly had other things to focus on.

However, one positive came from it… as we see from the cast list. The original West End production featured Joan Hickson in the role of Miss Pryce. According to Agatha Christie Limited, Christie was so taken with her performance that she wrote to Ms. Hickson and stated that she hoped she would one day play the character of Miss Marple. While it took 39 years to come true, Joan Hickson was finally cast as Miss Marple in 1984. For aspiring female actors, this is the clearly the role to take!

While Samuel French obtained the publication rights in 1947, a playscript wasn’t published by them until 1956. Since her agent, Hughes Massie, did not actively promote this play for amateur production, very few playscripts appear to have been published in the initial print run – making the first printing exceptionally difficult, potentially even the hardest, to find. For those that can find one, you’ll be pleased to know it does contain photographs of the original set designs.

1945: Towards Zero – Outside (adapted by Christie)

The next play to reach the stage was the only play Christie wrote as a result of a commission. The Shuberts in the US, who had produced several of her plays already, commissioned a stage adaptation of her recently published novel Towards Zero. This play was the first to premiere in North America. It opened on 4-Sep-1945 at Martha’s Vineyard Playhouse. However, it has not been professionally produced since.

In fact, this was considered a “lost play” until its script resurfaced based upon research in 2015 by Dr. Julius Green for his wonderful book – Curtain Up – a must read for anyone interested in the history of Christie’s plays. This play is not to be confused by the later adaptation written mostly by Gerald Verner but with some minor input by Christie. To differentiate, Christie’s original adaptation is often referred to as Towards Zero – Outside because it is set on the terrace, while the later adaptation is referred to as Towards Zero – Inside, as it is set entirely inside Lady Tresselian’s home. So many fans of Christie are awaiting a stage production of this original Christie-penned version.

When the playscript was approved for publication a few years ago, Samuel French first issued it as a large format comb-bound printing. For collectors there are no vintage publications to acquire. Perhaps there’s a programme out there somewhere from Martha’s Vineyard, but I’m yet to find one.

1951: The Hollow (adapted by Christie)

The Hollow was the next play Christie adapted that appeared on stage. It opened at the Art’s Theatre in Cambridge in February 1951 although Christie was absent as she was in Iraq accompanying her husband Max Mallowan on one of his archaeological expeditions. As with her other plays, Christie adapted the story heavily – such as removing Poirot. In The Hollow, which has some excellent comedic banter, there was obviously some concern that a director may make the play too funny so one of the stage directions related to the Inspector is “He must not be played as a comedic part.” As with other Samuel French printings, the original playscript does have a photo of the set showing the garden room of Sir Henry Angkatell’s house.

After a brief test run in Cambridge, it re-opened in Nottingham in May 1951, and went on a three-week tour prior to moving to the West End. The last stop on this tour was at the Theatre Royal in Birmingham. Promotional flyers for that final stop are informative because they show how the producer, Peter Saunders, tried to overcome the reality that he didn’t have any big-name stars in the play. The lead was given to Jeanne de Casalis – a comedic radio star from the 1930s – while other parts were given to actors who were promoted to sound more famous than they were.

The play opened in the West End at the Fortune Theatre in London on June 7, 1951 – but it only stayed there for four months – making the original programmes scarce survivors. The programmes are also highly desirable for collectors as this was the first play written by Agatha Christie that Peter Saunders produced. After the Fortune, it transferred to the Ambassadors Theatre in October where it ran for a total of eleven months before closing.

The Hollow was considered a success by Christie – even Queen Mary attended a performance. At the end of 1951, while it was still playing at the Ambassadors Theatre, Peter Saunders received the script from Christie for her next play – The Mousetrap.

1952, October 6: The Mousetrap (adapted by Christie)

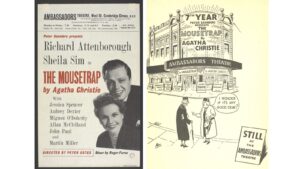

The Mousetrap was first performed at The Theatre Royal in Nottingham on the 6th October, 1952. This was its first leg on a seven-week tour in advance of moving to London.

The play was adapted by Christie from a short radio play she wrote that was first aired in 1947, which was itself inspired by real life events.

The first playscript was published by Samuel French two years later – in 1954. Included was a photograph of the original set design for The Great Hall at Monkswell Manor – not a lot has changed over the years for those who have been more recently.

Material related to The Mousetrap is probably the most widely collected – due to both its popularity and because of how long it has run. When one considers what a success it is, it’s interesting to see the programme for its first performance at The Theatre Royal in Nottingham which solely had a ballerina on the cover! If only they knew.

When the play opened in London on 25th November 1952, its new home was the Ambassadors Theatre, and the cover of the programme had an image of a mousetrap – but no actual title. The earliest programmes with Attenborough and Sims in the cast and the programmes from the advance tour are all highly collectible.

Other collectibles from the early years are original posters which gave the real-life married actors Richard Attenborough and Sheila Sim top billing. With Saunders’ success with The Hollow, he was finally able to attract these big stars that he wanted – and there’s little doubt that their billing launched the play successfully and gave it legs. Unique silk programmes were issued to commemorate special moments – a theatre tradition that dates back to the 18th century. There were special programmes that recognized the 1000th performance, and also the 2239th performance – when The Mousetrap became the longest running theatrical show in London’s West End, eclipsing the show Chu Chin Chow from almost 30 years earlier.

One cartoon from 1959 I particularly like shows the theatre with numerous billboards and displays noting the play has been going for 7 years and is still running with over 2,600 performances – while one lady asks another, “I wonder if it’s any good, dear.”

The Mousetrap was first performed in the United States on the Arena Stage inside the Hippodrome in Washington D.C. It was a theatre in the round and the last play to be produced at this historic theatre – where it ran for eight weeks.

Before the play made it to New York, it was performed in various other venues in the USA. The play didn’t get its official Broadway debut until November 1960 when it opened at the Maidman Playhouse where it played for three months, before moving to the Greenwich Mews Theatre where it lasted two more months before closing… so five months in total for its Broadway run… certainly not the same legs as London.

1953, September 28: Witness for the Prosecution (adapted by Christie)

Witness for the Prosecution was adapted by Christie from a short story originally titled “Traitor Hands.” As did The Mousetrap, this play also opened at the Theatre Royal in Nottingham. Its first performance was the 28th September 1953. It then travelled to Glasgow, Edinburgh and Sheffield before moving into its West End home at the relatively large Winter Garden Theatre on the 28th October 1953.

The first playscript was published by Samuel French in 1954 and, unlike most playscripts, this had an “author’s note” from Agatha Christie, who was concerned that the almost 30 actors required would be too much for amateur performances – so she provides insights on how to reduce the number of actors needed. One of these suggestions is to have members of the audience invited on stage and use them in non-speaking roles – such as in the jury. This is something the current production at County Hall in London has taken a step further, as you can now pay extra for the privilege of sitting in the jury box.

The first printing of the playscript also includes photos of the two sets needed for this play – the first being the Chambers of Sir Wilfrid Robarts, Q.C. and the second being the Old Bailey or Central Criminal Court.

For collectors of programmes – the original programme from the Winter Garden Theatre is quite different from earlier plays with its photo on the cover.

Given the success of Christie’s plays and their star-maker abilities, the inside of the programme contains numerous pictures of the actors at work. David Horne, who played Sir Wilfrid, had previously been in ‘Murder on the Nile’. Patricia Jessel – relatively unknown prior to this – became a huge star because of her role as Romaine. The play continued at the Winter Garden until January 1955 when it closed after 458 performances.

The play opened in the States originally in New Haven, Connecticut, in November 1954. Patricia Jessel had left the West End production mid-run and gone to the States to perform in this US production. For the role of Sir Wilfrid, Peter Saunders hired Francis Sullivan – the actor who had played Poirot in Black Coffee 24 years earlier. The play opened at the Henry Miller Theatre on Broadway on the 16th December 1954.

In the States, the phantom actress who played the “other woman” is Dawn Mathison – again one wonders how the name was chosen.

1954, September 27: Spider’s Web (original)

The next Christie play to reach the stage was only her second fully original play – the first being Black Coffee from 1930. This new play was Spider’s Web and was first performed at the Theatre Royal in Nottingham in September 1954. Samuel French published the playscript in 1956. Fortunately, Samuel French was still providing a photo of the original set design – which for this play was the drawing room of Copplestone Court – the Hailsham-Browns’s home in Kent.

The genesis of this play is rather unique. Herbert de Leon was the manager for the film actress Margaret Lockwood, who was Britain’s highest paid film star in the 1940s and early 1950s. She had become interested in moving from film to stage, so de Leon contacted Peter Saunders and suggested to him that he ask Agatha Christie to write a play specifically for her to star in.

When Christie and Lockwood met to discuss the idea, Lockwood requested that she didn’t play a sinister or wicked part but wanted a role in a “comedy thriller.” They clearly had a great respect for each other as successful women. There is a great quote from an interview Lockwood gave to the press where she says: “Agatha has the gift of doing what all women want to do, but only men have a chance …. The only consolation I get is that Agatha kills off a few of you.”

Spider’s Web opened in London at the Savoy Theatre on the 14th December 1954. The original programmes clearly put Margaret Lockwood front and center as the star with her head shot on the cover.

It’s worth pausing for a second to note that when Spider’s Web opened at the Savoy, Agatha now had three plays running simultaneously in London’s West End – this, The Mousetrap and Witness for the Prosecution. This was a new record for a female playwright. While Witness for the Prosecution closed in January 1955, Spider’s Web continued for almost two more years.

However, Margaret Lockwood left the cast in May 1956, after 15 months in the role. A suitable replacement was needed – preferably another film star. The role was given to Anne Crawford, both a film and television star of the day, but also the wife of the director Wallace Douglas. But her role was short lived – Anne died from leukemia in October that year, resulting in the play closing shortly thereafter. For collectors, the promotional ads and programmes from Anne Crawford’s stint are much rarer than those of Margaret Lockwood.

One last challenge for Peter Saunders was that he’d committed to two weeks of performances off the West End once the play’s run ended. Margaret Lockwood saved the day for him – resuming her role for these last performances.

1958, February 24: Verdict (original)

The next Christie play to reach the stage was an original play – initially titled No Fields of Amaranth, it premiered under the name Verdict. Unlike the previous few plays, its premiere was not in Nottingham but at The Grand in Wolverhampton, in February 1958.

The first playscript was printed by Samuel French in September 1958. The first printing still contained a photograph of the set design – the living room of Dr. Hendryk’s London flat. The décor for this set was done by Joan Farjeon – the same lady who designed Sir Henry Angkatell’s living room for The Hollow seven years earlier.

The original flyer for the world premiere in Wolverhampton gives top billing to Patricia Jessel – reminding us of her role in Witness for the Prosecution – not only in London but in New York, where she won a Tony award for her performance. The flyer is also very transparent in stating that the play “is not a whodunit.” However, when the play opened in London at the Strand Theatre on 22nd May 1958 – it was to poor reviews, and Patricia Jessel’s presence could not save it, as many theatregoers were expecting more traditional Christie fare. For those who have read Verdict, you know it is more of a traditional play – there are no secrets or surprise endings – things that audiences likely expected. Consequently, the play had a very short run, closing within a month of opening. This is another wonderful play that is unfortunately not produced often enough.

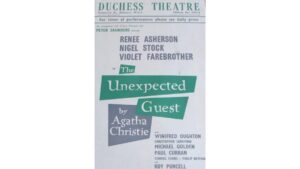

1958, October 4: The Unexpected Guest (original)

Given the publics disappointment with Verdict, Saunders and Christie realized the best solution was to stage another play as quickly as possible – this time one in a more traditional Christie style. The play was The Unexpected Guest. It was first performed on the 4th August 1958 at The Hippodrome in Bristol. It played for only one week before moving to the Duchess Theatre, in London’s West End, where it opened on the 12th of August.

The speed with which Christie and Saunders accomplished this is shocking and likely something that couldn’t be replicated today. Verdict closed on the 21st June, but by the 14th of July – less than 3 weeks later – Christie had resurrected a previously conceived play and finalized its script. Cast members were signed, Hubert Gregg hired to direct it, and rehearsals had begun. Within a month of Verdict closing, the trial run in Bristol had been completed and the play was now in the West End.

The photograph of the set design in the first Samuel French printing starts to give a hint as to the style Christie was returning to – with its country house vibes – almost harkening back to The Hollow. The opening of the play with the curtain being raised to a dead body on stage, shot through the head, instantly tells the audience this may be more of a traditional Christie.

The play saved Christie’s reputation. The critics and audiences loved the play, which ran for almost two years and broke all box office records at The Duchess Theatre. Even the Queen went to see the play in early 1959. The Unexpected Guest finally closed in January 1960.

While we could continue to discuss Christie’s plays for hours, what we have already covered marks essentially the first thirty years of Christie on stage – from Alibi in 1928 to The Unexpected Guest in 1958. Given our look back over this period, I’d like to share an excerpt from a letter that was recently auctioned. It was a reply to a fan written by Agatha Christie in 1929 – shortly after Alibi was performed. As you can see, it reads: “I hope to have another play on sometime. But plays are very uncertain things. Thank you for all you say about my books. It is always nice to know one’s work is appreciated.” Little did she know then what a success she would become as a playwright and how much her work continues to be appreciated today.

Closing Comments

There are still many plays we haven’t talked about today, but we’ll just have to save those for another time. I should also point out that all the plays we’ve discussed today, as well as many others, are being published and are available from Samuel French. There are still many unpublished plays, and hopefully one day they will also be available for fans to acquire and read.

What I do want to end on, though, is how important it is to explore the world of Christie on stage – whether by reading the plays yourself or seeking out plays to attend. There is so much more to the world of Agatha Christie than just her novels.

If you are interested in all things Agatha Christie, then please visit our website – CollectingChristie.com – where you can find numerous articles like this one discussing many aspects of her world.

Newly Available for Licensing – January 2026 (UK)

Newly Available for Licensing – January 2026 (US)