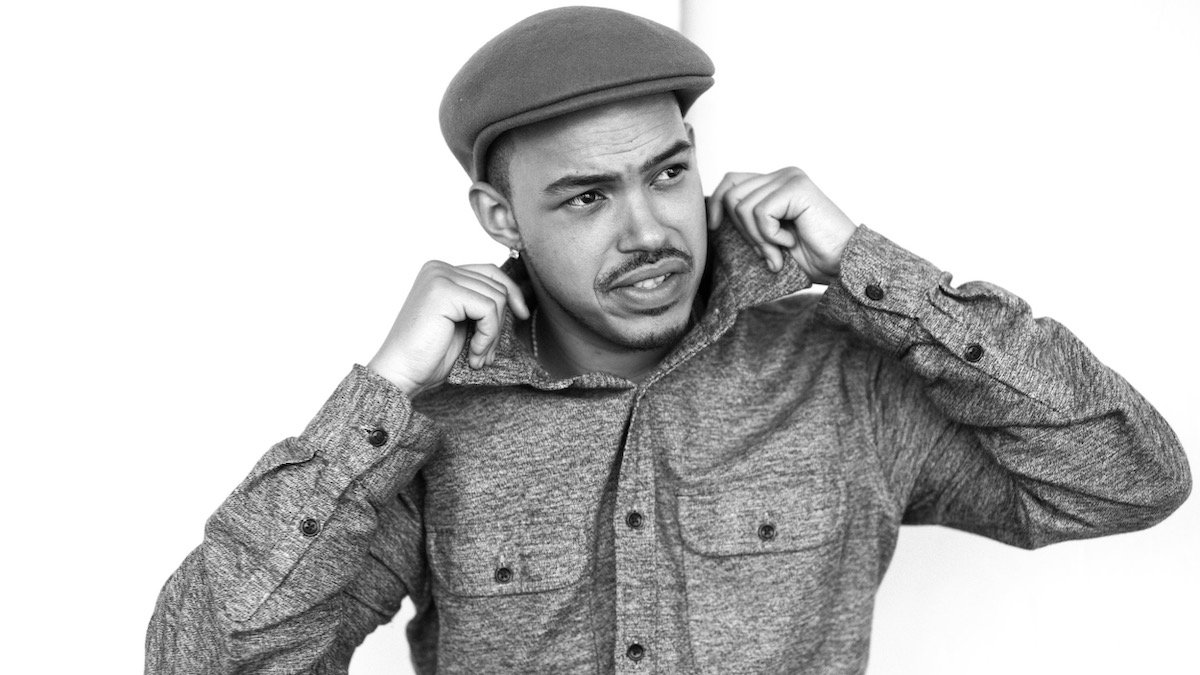

Nominated for a 2022 Olivier Award and shortlisted in 2017 for both the Bruntwood Prize and Alfred Fagon Award, Archie Maddocks’ bittersweet comedy A Place For We holds a mirror up to the ever-changing face of London’s communities. Set in a single building in Brixton – which evolves from pub to funeral parlour to urban-zen enoteca and conscious eatery – the play tells the story of three very different generations. We spoke to Maddocks about his play, his influences, and his dual roles as playwright and stand-up comedian.

…

Describe A Place for We in a few sentences.

A Place for We is a play about legacy, tradition, family, gentrification and honour. It’s about the things we hold onto when we don’t really know why, and it’s about the pressure of the past becoming too much for some people as it no longer applies in a very different world. It’s about what people can pass on, whether it’s physical things or metaphorical lessons.

Where did your inspiration for the play come from?

I was working in a funeral home at the time and became very interested in the different funeral rites from different cultures. Around the same time, an auntie of mine died and we held a nine night, which was the first one I can properly remember, and I thought about how this might not be around too much longer as people with a Caribbean background but born in the UK might not keep the tradition alive. At the same time, I was starting to notice gentrification in Brixton. I thought that it was something I should write about and then, I guess, all those things sort of came together.

Why do you feel that the stories in A Place for We need telling now?

Well, in a way, I think that they’re timeless stories at the heart of it, so I hope that in years to come people can come back to the play and still find things in it that resonated today. I guess I felt like I needed to honour the old Caribbean generation, the “Windrush generation” – they were so unique and powerful and proud and there’s never going to be another generation like them, and I thought it would be interesting to look at some of the discussions and arguments that take place amongst my families and friends. Everything changes with time, and the old always clashes with the young, that’s a thing that’s going to keep happening because that’s life is. For so many, the realisation that they’re going to have to make way for someone new to come in is an impossible concept, and I thought it would be fun to play with that.

What advice would you have for companies looking to stage the show in future?

I would mainly say just to have fun and find your voice and your vision in it. I’ve done my ting now; this is for you. It can be whatever you want – you don’t have to listen to my written suggestions at all – make it yours. But also, don’t make it shit, I beg. That would be ideal.

Are there particular playwrights of theatre makers who have influenced your work so far, or the type of work that you want to make?

I really like the big American plays – Death of a Salesman (US/UK), Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? (US/UK), A Streetcar Named Desire (US/UK). They have this wonderful ability to make the everyday so epic, to make the life of one person mean so much. I think there’s a tendency at the moment to lack ambition, but I want to write big ambitious plays like the greats have done. I think what I enjoy most about those plays is that they’re summed up within the first minute or so – Death of a Salesman’s Willy says he’s tired to death, and then what happens in the end? For me, that’s great they’re telling us exactly what’s going to happen, and then it does, and it still feels like a big journey with a heartbreaking conclusion.

Alongside playwriting, you’re an active performer on the stand-up comedy circuit. How does one craft influence the other?

They both feed into each other, really. Stand-up really relies on the audience and their involvement in what I’m doing – if they ain’t laughing, it’s a one man show that no one paid for – so I think it’s been really helpful in understanding what an audience wants and needs. And theatre gives an understanding of pacing and tension, which over the course of a stand-up hour can be the difference between people staying with you or tapping out after 45 minutes. I think both things teach you the value of picking your words carefully, and how the economy of words can have a big effect on what people get out of the thing you’re trying to do. Stand-up, for me, is the purest art form (Is it an art form?) in that you know immediately if people are enjoying what you’re doing – if they like it, they’re laughing (unless they’re inside laughers but comedians hate them) and that immediacy is so valuable to me. I try to inject the pace and energy of stand-up into everything that I write.

…

To license a production of A Place for We, visit ConcordTheatricals.co.uk.

Women and Show Biz: A Conversation with Playwright Peter Quilter

A Pan of Buttermilk Biscuits: Purlie Victorious and Sustenance