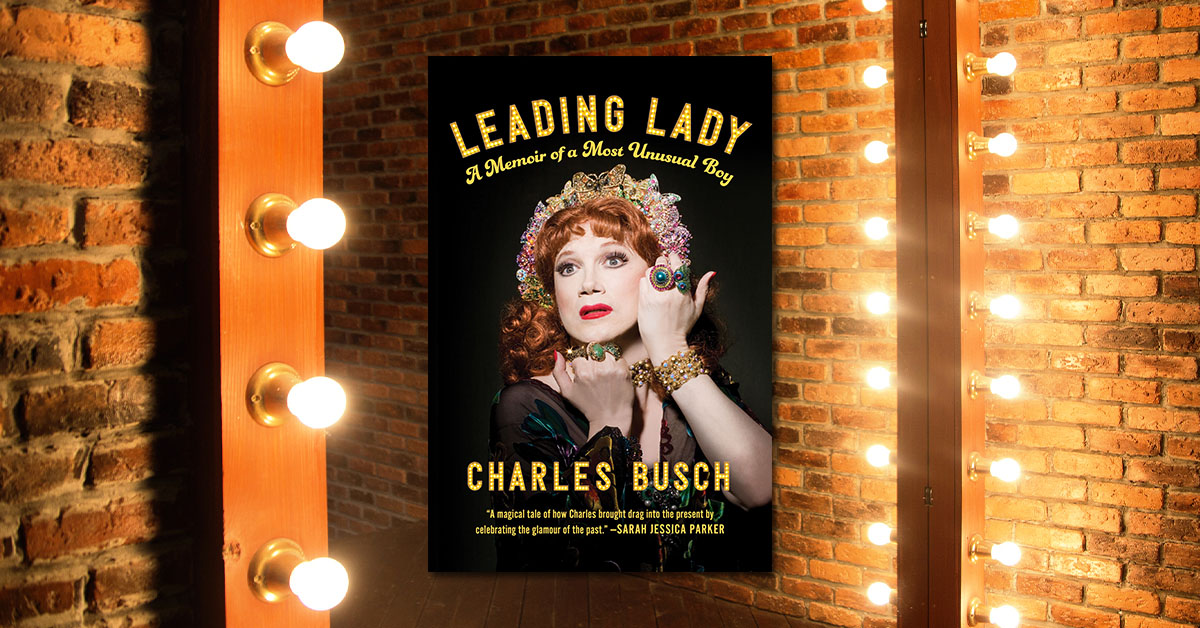

Award-winning playwright Charles Busch is a master of genre-specific camp with a light touch and huge laughs. His numerous off-Broadway comedy hits include The Confession of Lily Dare, The Divine Sister, The Lady in Question, Red Scare on Sunset and Vampire Lesbians of Sodom. On Broadway, his play The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife earned a Tony nomination for Best Play, and it remains the longest-running Broadway comedy of the past 25 years. He also wrote and starred in the film versions of his plays Psycho Beach Party and Die Mommie Die! Busch continues to write great comedies, including his newest, Ibsen’s Ghost.

Theatre legend Charles Ludlam founded the Ridiculous Theatrical Company in 1967 when he was just 24 years old. For the next two decades, until his AIDS-related death in 1987, Ludlam wrote, directed and performed in nearly every Ridiculous production, often with Everett Quinton, his life partner and muse, by his side. Renowned for drag, high comedy, melodrama, satire, precise literary references, gender politics, sexual frolic and a multitude of acting styles, the Ridiculous Theater guaranteed a kind of biting humor that could both sting and tickle. Ludlam’s many plays include Bluebeard, Der Ring Gott Farblonjet (a riff on Wagner’s Ring Cycle), Turds in Hell (an adaptation of Satyricon) and The Mystery of Irma Vep, his most popular play and a performer’s tour-de-force.

In his recent memoir, Leading Lady: A Memoir of a Most Unusual Boy (Smart Pop, 2023), Charles Busch reflects on his eclectic, hilarious and astonishing career in the theatre. In this chapter, reprinted with permission, Busch recounts the moment when he first encountered Ludlam, marking the union of two brilliant theatre greats.

Rubbing Shoulders in Chicago

It was 1976. Charles Ludlam and the Ridiculous Theatrical Company were appearing at the University of Chicago, presenting two plays in repertory, Camille and Stage Blood, as well as conducting a Saturday afternoon workshop. Ed and I, wrapping up our senior year at Northwestern, snapped up tickets to both performances. The university campus on the South Side of Chicago was a big schlep from Evanston where we were living. Neither of us had ever been to the South Side, but we weren’t going to let a mere thing like geography deter us from seeing both plays and attending the workshop.

Friday night was Camille, with Ludlam playing Marguerite Gautier in his comic adaptation of the Dumas classic. The play stayed true to the structure of the original and managed to be both parody and infinitely moving. Charles worked several miracles. He had thick masculine features and yet his eyes were beautiful for any gender, luminous and dark. A black wig of nineteenth-century corkscrew curls and full drag makeup couldn’t make him pretty, but his acting skills and charisma made you believe he was a great beauty. His art was not about trickery and illusion—he was quite simply an incomparable Lady of the Camellias with a hairy chest.

The following day, Ed and I took the L back to the University of Chicago to attend the workshop. We didn’t know what to expect. Would we be participating in some sort of improvisation or working on scenes? It turned out to be a conventional question-and-answer format. With about a dozen people present, a dismally pedantic moderator conducted the interview.

To be fair to the interviewer, Charles was not a lighthearted subject. He was a serious and articulate theorist on his unique style of anarchic theatrical parody and resisted all attempts by the moderator to place him within the context of drag queen entertainment. At one point, the moderator referred to him as a transvestite, which did not go over well. The interview was then opened to questions from the audience. The questions were either pretentiously academic or simplistic to the point of idiocy.

I raised my hand and asked Charles something specific relating to the 1936 Garbo film of Camille. Whatever I said went over well and Charles was able to give it a full answer. When the interview concluded, Ed and I approached Ludlam, and he thanked me for helping him out with a thoughtful question. As only someone so young and ambitious would, I’d brought with me as a gift a poster of Sister Act, the play Ed and I were about to perform on campus. As soon as I handed it to Ludlam, I thought, Oh, he’s going to toss this in the trash. Several members of his company were present, among them Georg Osterman, who played the female ingénue roles. He was younger than the rest, closer in age to Ed and me. Georg was naughty fun, and after we finished dishing all the dreary attendees of the workshop, he suggested that we stick around after the performance that night and go with the company to a closing night party at the home of a wealthy philanthropist.

There was no time to return to Evanston, so Ed and I sat for hours in a coffee shop before that night’s show. Stage Blood was a backstage comic thriller about a touring production of Hamlet. Much of the play took place in a theatrical dressing room. As the lights came up, Ed and I gasped – our Sister Act poster had been taped to the wall of the set. It was possible that I’d made a favorable impression on my idol, but more likely they simply needed something to decorate a blank wall.

Before anyone could leave for the party, the set would have to be struck and the costumes and props packed away. It was only good manners to help. The stage manager suggested that I take the costumes off the rack and fold them into a trunk. I removed and packed several costumes and then saw that the next costume on the metal rack was Charles’s first act ball gown from Camille. I lifted it gently off its hanger. To smooth out the costume, I had to press it against myself. I looked up to see Charles observing me. We were in the exact positions as Anne Baxter and Bette Davis in the scene in All About Eve where Margo Channing discovers her scheming young assistant, Eve, posing with her stage costume. There was a sizzle of electricity between us, almost as if all the lights in the Midwest blacked out for an instant. If we’d known each other, we might’ve laughed at the visual accuracy of our re-creation.

The closing party was held in a majestic townhouse. As the crowd was thinning, Georg ran outside and around the building until he was just below the window facing a table full of wine and whiskey bottles. When the coast was clear, Ed and I tossed the bottles to him for a late-night party back at the hotel where the company was staying. Once there, the two women in the company, Lola Pashalinski and Black-Eyed Susan, retreated to their room and Charles and his lover, Everett Quinton, in the first blush of their romance, went directly to theirs. Ed and I hung out with Georg, the tall, cadaverous character actor John Brockmeyer, and Ludlam’s dissolute leading man, Bill Vehr.

Ed and I, feeling rather like genteel Miss Porter’s finishing schoolgirls, found Bill and John’s camp humor to be on the disgustingly scatological side. It grew late and we were anxious about getting back to Evanston on the L. Georg suggested we bunk down with them at their nearby hotel. Since Georg had only a small single room, Bill and John chivalrously offered to let us spend the night in their larger suite. There was nothing sexual in the invitation. The fellas didn’t find Ed or me any more delectable than we found them, and the night I spent sharing a narrow single bed with John Brockmeyer passed with our backs to each other and both of us sound asleep.

Bill and John seemed so much older than us, yet there was most likely only about an eight-year age difference. I wondered if Ed and I were a new breed of post-Stonewall gay men—John and Bill the renegade outlaws, and we the young city dwellers about to change the tone of the frontier. Being gay in New York in the pre-Stonewall sixties couldn’t have been all grim: There was Judy at Carnegie Hall and Callas at the Met. I’m sure there was some satisfaction in being part of a secret society, with its own transgressive slang and sexy inside humor. Still, one would be subjected to police raids on gay bars and being patronized, marginalized and ridiculed as a minority not worthy of any consideration.

The Stonewall Uprising gave gay people a new identity, no longer as pathetic victims or the subject of dirty jokes but as a fierce political entity. That activist spirit made it hip to be gay. Or even gay-adjacent: Bette Midler’s rise to fame performing in a gay bathhouse and Liza Minnelli’s Oscar-winning performance in the film Cabaret took the desperation and poignancy out of the role of “fag hag.” A straight woman could run with a gay male crowd and not be a sad drone but the fabulous Queen Bee. Coming of sexual age in the early post-Stonewall 1970s, Ed and I experienced none of the furtive paranoia of our recent predecessors and blossomed in the new gay chic of urban life.

Reprinted with permission from Leading Lady by Charles Busch (Smart Pop, 2023). Purchase your copy of Leading Lady here.

To license a production or purchase a script from Concord Theatricals, explore The Charles Busch Collection and The Charles Ludlam Collection.

Comedy Mysteries: Gasps, Laughs and Thrills

A Children’s Theatre Classic: An Interview with Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs Composer Michael Valenti