Directing is elusive. There is something ephemeral and fleeting about the art of directing. You can’t read it, hold it in your hands, or e-mail it. It must be felt. Direction lives in the thin space between the play and the audience—the exchange of performer and spectator. It lives in the freedom and rigor of the physicality of the performers and in the detail of the design world that ensconces the text. Directing lives in the tone of the play and in the perspective by which we view the play.

Pass Over is an ideal text, both extremely challenging and endlessly inspiring. The language is written with almost no punctuation, but plenty of line breaks, almost like a poem. The language has it’s own heartbeat: sometimes it speeds up, quickening with fear and anticipation of terror, sometimes it slows down until you almost can’t tell if you can even hear the heartbeat, when all of a sudden it returns pounding, sending blood into your ears and making you sweat. There are very few stage directions, allowing the language to inspire physicality, as opposed to being prescriptive. The playwright has confidence enough in her craft to trust her collaborators, and that trust extends to her audience; she never condescends, always draws them in, hypnotizing them with language, humor and humanity before confronting them with the bracing light of truth.

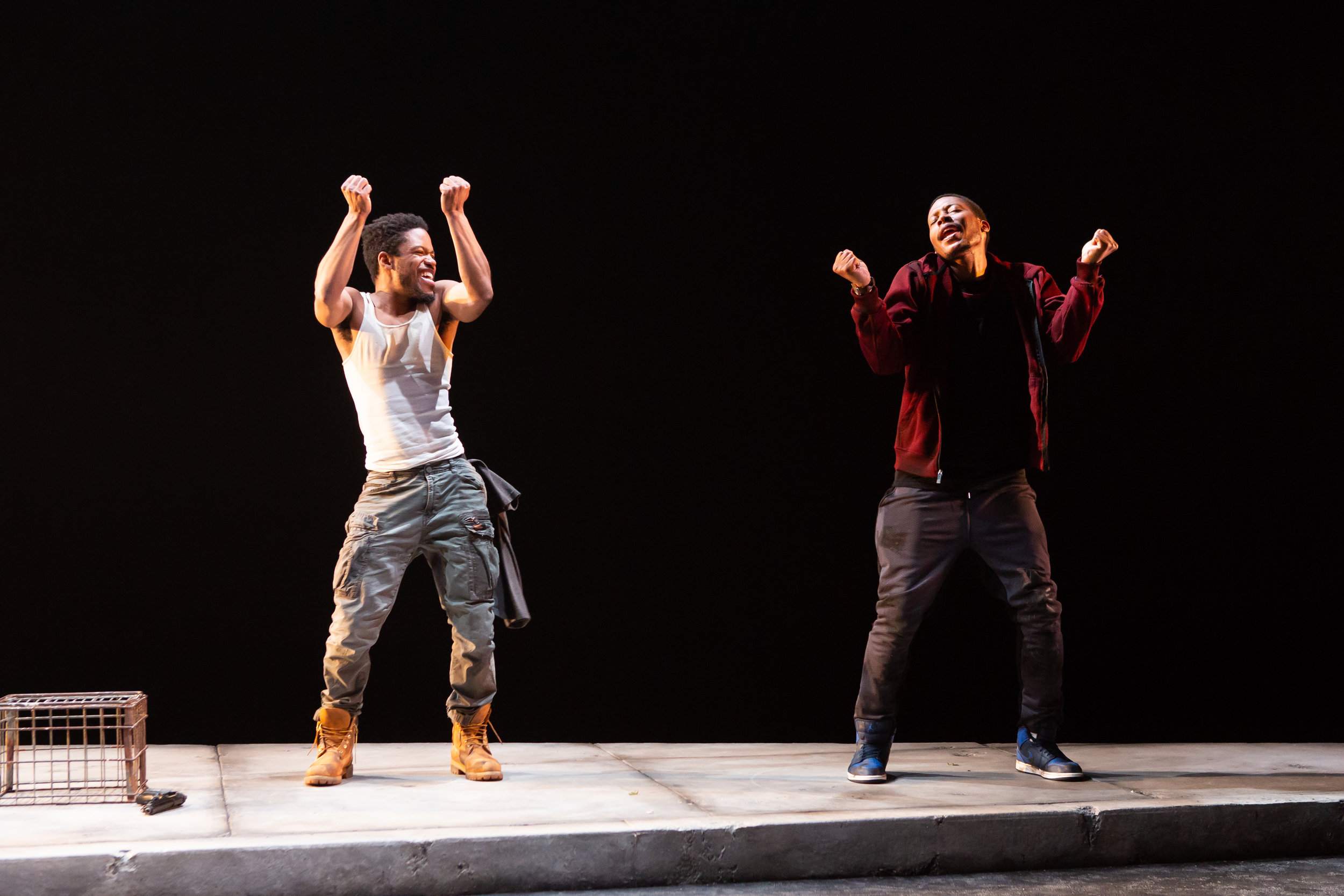

LCT3 production of Pass Over

When Antoinette and I first sat down to begin our work on Pass Over together, we spoke at length about the perspective from which the audience would view the play. We knew that our audiences, at least at first, would be the typical theater audience: overwhelmingly white, upper class with liberal leaning tendencies. How could we invite this audience to see the world from the perspective of the plays heroes, two young African American men named Moses and Kitch? To acknowledge their part in the endless cycle of violence against young black men. We did not want to alienate the audience, on the contrary, we knew we had to invite them in slowly, get them on the ride of the play, and never let them step off until the final blackout. This led us to our preshow: When the audience walks in, Moses and Kitch are already on the stage. We knew it was important for the audience never to have the opportunity to see the stage bare, for in reality, these young men are always stuck in their state sanctioned purgatory. While Moses sleeps onstage, Kitch keeps watch. In the house of the theater, classic 1950s show tunes play. This is, of course, employing irony, but also something more: These songs are from the classic musicals Antoinette listened to as a young girl, visions of happiness and American dreaminess that seemed so close yet impossible to reach: The Promised Land. It was important to us at every moment to show the disparity between that majestic dream and the reality for these young men.

The design of the play is extremely sparse, “essentialist” rather than “minimalist”. In rehearsal we experimented with a variety of props, but by the time we reached previews, I had cut everything other than what was truly essential for the action of the play: two metal crates, a tire, a rock, and a deflated basketball. This essentialism forces the audience to locate warmth and humanity in our two protagonists, Moses and Kitch. For the first 15 minutes of the play, there is no white character for white audiences to see themselves in. It was endlessly fascinating to observe that when the white character did walk in for the first time, if our audience was mostly white, you could feel the audience relax and begin to engage vocally. When our audiences were more mixed, something magical would happen. People would notice someone next to them having a different experience than they were having, and this would create a buzz within the audience that was palpable. Pass Over, more than any play I have ever directed, is written for the theater, to be played live, to provoke a discourse, to create true feeling and discomfort.

Thus far, I’ve had the opportunity to stage the play three times: first in Chicago at Steppenwolf Theater, second for Spike Lee’s filming of that production for an audience of mostly young black men, and recently in New York at LCT3/Lincoln Center Theater. As a director, getting to revisit and refine your work is an extremely rare and thrilling opportunity. Antoinette and I both felt extremely proud of our work in Chicago, but knew we both had some things we wanted to improve in our New York production. These improvements were about clarity, precision, rhythm and adapting the performance for a more intimate space. A new ensemble of actors brought a different humanity to the play. I led an hour long physical warm-up at the beginning of each rehearsal day, rigorously reexamined every staging and design choice we made in the first production, and adapted to a New York audience, who differ from their Chicago counterpart. This reexamination led to a physical language and vocabulary that matched the power of the text, harkening back to its Beckettian influences, heightening the power of the production.

LCT3 production of Pass Over

Pass Over is a timeless text, evoking terrors past and present. The onslaught of bad news is seemingly never ending, and sometimes we listen to it and sometimes we are deaf to it. But the play sheds light on this darkness, on this deafness, implicating the audience as a participant in the seemingly unending absurdity that is white supremacy. By showing the world through the eyes of two young black men, Pass Over reveals the value of a human life and the responsibility that we as a people, must take for our fellow human beings. The playwright Jonathan Payne wrote a deeply moving note to Antoinette and I after watching the play, “I was yanked here then there, and then back again. Actually experienced CATHARSIS! Like actually experienced this mysterious thing that’s talked about in textbooks, or theatre books. But it’s like a BLACK CATHARSIS (which, of course, gets snatched away). Not a white folk catharsis. I don’t think it hits them in that way, much like watching a Greek play for me.” A few white audience members found the depiction of the two white characters to be unfair or cartoonish. Perhaps to their eye or experience these characterizations seemed to be an exaggeration, but when you step into the shoes of Moses and Kitch, you realize that these depictions are disturbingly realistic for these young men, terrifying and bracingly real. Pass Over challenges its white audience to accept that the way they see and experience the world is not the only way the world is seen and experienced.

As Hannah Arendt writes, “Because the actor always moves among and in relation to other acting beings, he is never merely a “doer” but always and at the same time a sufferer. To do and to suffer are like opposite sides of the same coin, and the story that an act starts is composed of its consequent deeds and sufferings.” Pass Over, despite the harsh realities it depicts, actually evokes a world of beauty, the power of love, and the necessity for us to find meaning and community through engagement and resistance as we confront our worst fears. This play has us believe profoundly in humanity and asks that its audience wake up and fight, even during the most hopeless of times.

To purchase a copy of Pass Over, click here, and to learn more about licensing a production, click here.

The Devil’s in the Details: Sharp Satire, Native Gardens and an Interview with Karen Zacarías

Newly Available for Licensing – January 2026 (UK)