“No one gives a sh*t about one-acts.”

He was lecturing me on not writing. On not writing enough of the “right” things. My playwright friend was trying to be helpful. But I wanted to tell him he was wrong. That he was just being clever. That his words wouldn’t hold up to scrutiny. That small can be big. And that big can come from small. I wanted to shake him. I wanted to shout, “You think great plays just grow on trees?!” But my pride shouted back, “Fin and Euba is published, ya know!” He just shook his head, repeating:

“No one gives a sh*t about one-acts.”

Bitter isn’t a good look on anyone. But I was bitter, and for a long time after that. His words haunted me, and the more I thought about them the more they seemed plain reckless. What terrible advice! We’re all out here in Play Submission Land trying desperately to decode the process, to figure out the system, to uncover the secret of how we get from here to there, and our go-to medium when we are first starting out is almost always the short form. And more importantly, it’s how we learn the craft in the first place. There is an art to the short form. Its atomic energy is highly sought after by myriad theatre practitioners as a learning tool and as a prime fuel source for self-discovery.

I’m not sure if specializing in the short form for over ten years makes one an expert in this area, but I will say that my periods of immersion into the short form have resulted in a collection of foundational pieces that I’m still building on today. They are how I came to know myself as an artist. Each little piece stands alone, as a little jewel (or lump of coal), in the universe. And as they came into being, audiences responded to some of them with an ardent plea: “That…whatever that was… more, please!” And of the utter failures: “You want my opinion? Let that one go.” I took it in. All of it. And I wrote more of the good and less of the bad. And eventually, a curious thing began to happen. The work that I felt most passionately about was the very work people were responding to. And so there came a kind of convergence, a happy arrangement between artist, product and consumer, all of us working together to support one another.

Fast-forward four years, and the “short plays” are all bearing fruit on the national stage. The Gulf won the Samuel French Off Off Broadway Short Play Festival and was subsequently published in three anthologies. It is scheduled to have its full-length world premiere at Signature Theatre later this month (directed by Joe Calarco). And my recently published collection, Love is a Blue Tick Hound, is about to receive its world premiere in my home state of Alabama at Terrific New Theatre.

It seems to me you don’t have to be a genius to understand the value of the short form. Tennessee Williams’ 27 Wagons Full of Cotton contains the seeds of what would become some of the finest works the world has ever known. Many established playwrights still work at the deceptively simple craft of packaging meaningful moments into small spaces: Craig Wright, Richard Dresser, and Lisa Kron’s short pieces have been produced at The National Ten-Minute Play Contest, ATL’s long-standing program (est. 1989) which “seeks to identify emerging playwrights.” David Auburn, Tina Howe and Romulus Linney have been featured in Ensemble Studio Theatre’s Marathon of One Act Plays, a prestigious long-running program known for its luminaries and star power. In a market that operates not unlike the U.S. Open, many production and publication outlets routinely feature A-list writers as well as emerging ones. In fact, my first successful short piece, Fin & Euba, is published in Best American Short Plays, right alongside Pulitzer Prize winner David Lindsay-Abaire’s Crazy Eights.

So you’re thinking, “Publications are great, festivals are great, but how do I get that?” I do not believe there is any shortcut to breaking out. And even if there were, I would question the efficacy of such a win. Just like athletes who start from the ground up and train and compete, improving with each round, gaining not just speed and momentum, but knowledge and wisdom, playwriting is best when we discipline ourselves to learn and grow with each step in the process. Here’s what worked for me…

Do Your Research

Work locally with your community theater to hone your craft and to build a following.

-

Establish a group of collaborators who want to encourage and foster your work.

-

Hold readings in your house, in coffee shops, over the phone. Just read the plays aloud. Listen to the advice, all of it – yes, even the bad advice – and take it all in. Respond, rewrite, read again.

Learn the festivals – all of them – local and national.

-

Submit to the ones that don’t charge a fee.

-

Keep records. I have a spreadsheet called “Who the f**k is reading my sh*t?” (no joke).

-

Some festivals (especially those in New York) will require you to self-produce. Do it! I’ve done it. Twice. Both competitions led to wins and publication in Best American Short Plays.

Keep submitting. Keep writing. And most importantly, keep questioning. Nothing is more vital than learning why you write.

Find Your Voice

In my early days as an aspiring writer, I knew I wanted to create strong roles for women and to make my pieces charming and meaningful. But there isn’t a playwright alive who isn’t aiming for the same thing. What I know now, through experimentation, trial and error, is that I want the pieces to be spare, distilled, and constructed specifically for a desired outcome of emotional release. I couldn’t have known this, let alone articulated it, after my first play.

I cannot stress this enough: through whatever means necessary — long form, short form, any form — you must write until you find your voice. In the early days it may seem like you are all over the map. This means you’re doing it right! Experiment with many forms, lengths, styles, and approaches and until you hit on a “formula” that works for you. It is in doing this that the “why” reveals itself, folding itself back over and informing the process as a whole. This “why” — also known as an artistic statement — allows us to embed ourselves into the landscape as a unique contributor to the great conversations of life: What is love? Why does it hurt? How does healing begin?

Get Help (No, Seriously, Get Help)

Playwriting should never be attempted alone. This is the surest way to fail. If you aren’t into collaboration, switch to another medium. Playwrights need actors, directors, and designers to help bring our plays to life. But more importantly, we need constructive irritants who will challenge the work and teach us what is possible. Brainstorming sessions, table reads, workshops, and talkbacks all offer a wealth of material and inspiration for expanding the scope and depth of a play. As we take in the viewpoints and perspectives of others, our work is enriched with truth and wisdom that is beyond our singular experience on this planet.

Write Like You Mean It

Whatever it is you stand for as a human being — and I don’t mean things like “gun control” and “social welfare” — I mean deep and intrinsic values that inform all of your decisions (e.g., integrity, empathy, loyalty), these are the drivers that compel us to share our stories in the first place. So, honor them not with didactic language, blustery monologues, flimsy setups, and crazy plot twists that no one cares about, but with genuine characters and predicaments that speak your truth via rich and meaningful exchanges. Insist on deeper conversation with yourself and with the watcher so that they see themselves reflected back to them in your words. If you do this, they will follow you anywhere. Even to a one-act play.

Also check out Audrey’s other essays on Breaking Character Magazine, Silence is Golden: The Electric Properties of Subtext in Playwriting and Advice to Emerging Playwrights: Keep it Cheap.

The Truth Behind… Gypsy

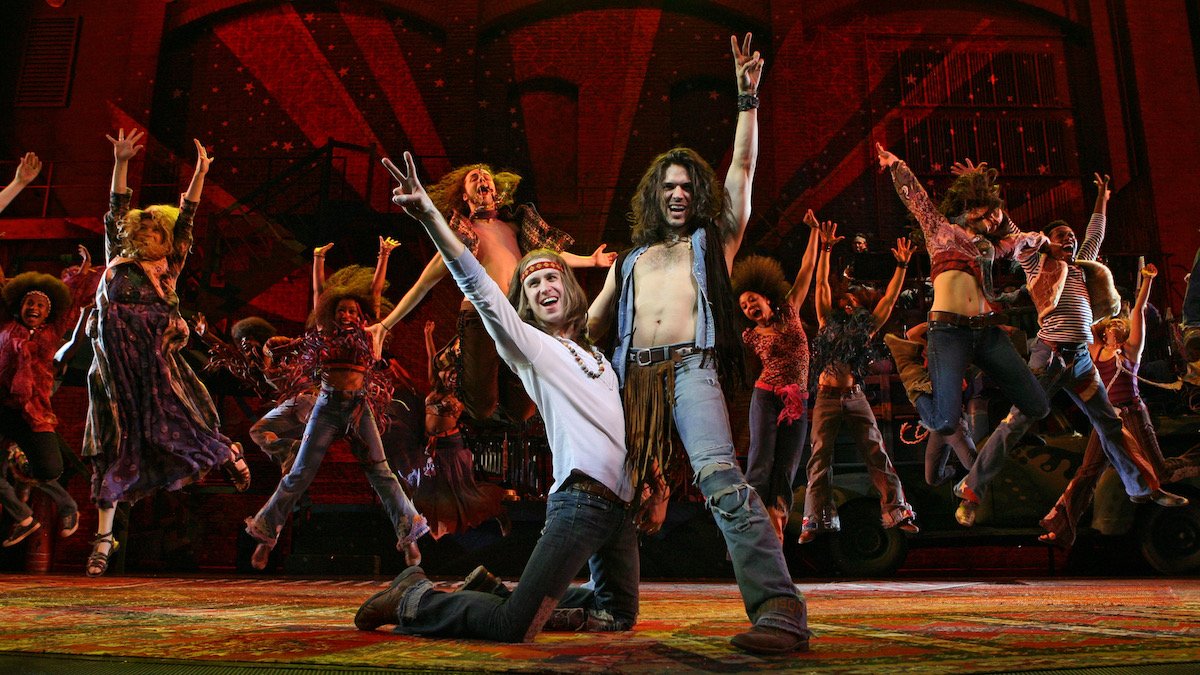

Pop/Rock Musicals