Garden District, based on a full-length play entitled Solitaire, is a short film by playwright, historian and educator Rosary O’Neill. Set in the lush and opulent Garden District neighborhood of New Orleans, Louisiana, the film tells the story of a very wealthy, very unhappy and exceptionally dysfunctional family.

To date, the short film has earned two awards and three additional nominations at the London International Film Festival, and won best production design at the Budapest Film Awards. Garden District has participated in additional festivals, including the Toronto International Women Film Festival, Montreal Independent Film Festival, Vancouver Independent Film Festival (Finalist), Berlin Shorts Award (Finalist), Vienna Indie Film Festival (Semi-Finalist), Florida Shorts (Semi-Finalist), Sydney Indie Short Festival (Semi-Finalist) and Paris International Short Film Festival (Finalist).

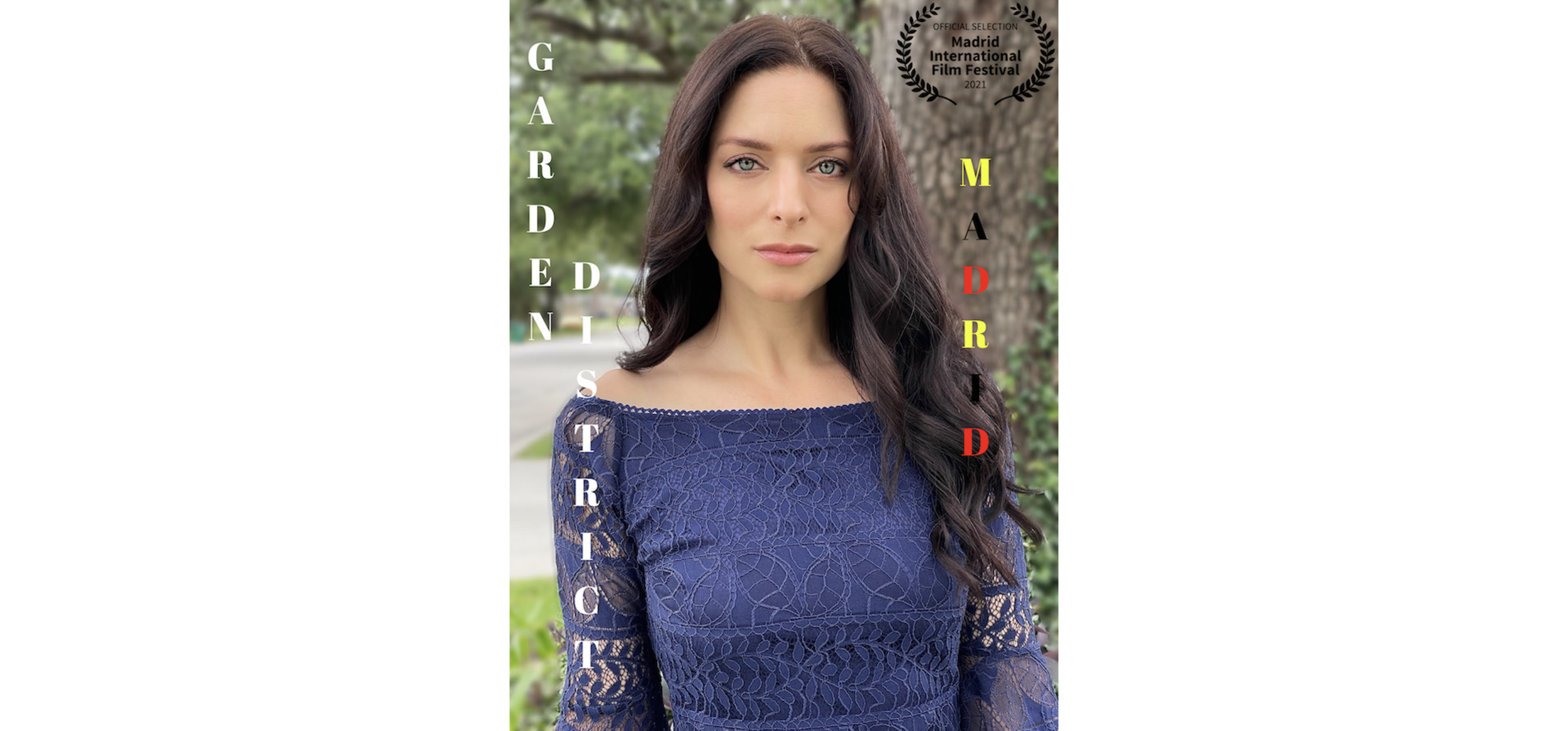

Recently, Garden District was nominated for five awards at the Madrid International Film Festival. These nominations include best short film, best director of a short film, best supporting actress in a short film, outstanding actress in a short film, and best set design. The event is virtual and will be held between August 23 and August 27 with the award ceremony taking place on August 27.

Mother/daughter team Rosary O’Neill and Rory Schmitt answered a few questions about this exciting project via an exclusive interview!

Rosary O’Neill and Rory Schmitt

Meagan Meehan: How did you come up with the idea for Solitaire, which later became Garden District? Did you grow up in that area?

Rory Schmitt (RS): We were raised in Uptown New Orleans in middle-class neighborhoods, but we were drawn to the glamor, allure and power of the Garden District. Daily, we drove past mansions shielded by towering iron gates, and regarded their residents as royals.

Rosary O’Neill (RO): My family lived on Carrollton Avenue and Fontainebleau Drive, “Uptown” being another term for the University area near Tulane and Loyola. We were mesmerized by the Garden District with its towering bananas, camellias, elephant ears, brick patios, verandas and secret gardens that kept most people out.

When I founded and ran Southern Rep Theatre in 1986 and had a Fulbright to Paris to write more plays, I learned that the people in Europe, France, Germany and England were equally intrigued by this world of New Orleans. I guessed that they were initially intrigued through Tennessee Williams, in such plays as Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Streetcar Named Desire, which address issues of yearning, corruption and loss of beauty.

There’s something about this culture that makes you feel you should always be beautiful and stylish, despite the heat. The foliage and the size of these rooms here with 21-foot ceilings and 14-foot windows are designed to keep out the heat—to let light in, and air pass through.

I wrote Solitaire on that first Fulbright to Paris. It was a way to somehow justify the corruption of money by excusing it with a veneer of beauty. My daughter, Rory, now a producer of Garden District, used to ask me to recite to her the opening monologue of the play. And I would. Now, for the Madrid International Film Festival, the lead actress in the Garden District film, Janet Shea, is playing the same role 25 years later in the film based on the play. Janet is nominated for the Outstanding Actress in a Short Film award, so I guess this world still has appeal.

You see, it’s about how we try to love each other and we hurt each other. How we grab and wound and run from Love. I think Europeans get the corruption and perversions of love and the onslaught to inner beauty that results. We Americans think outward beauty necessarily implies inner beauty, but often it is the opposite. Inner beauty comes from truth, goodness, virtue, love, God. But somehow that outer magnificence is also a shadow of the inner side of us that wants to come out and explode.

Solitaire (Garden District) is about the artists’ need to express that greater truth. Inner truth is what life is about, and in Garden District the world of the privileged New Orleans somehow grapples to find that truth. The young son artist, Rooster, played by Bryan Batt, deeply celebrates beauty, and his mother wants to support him but is at the same time hostile to art. Desiring and hating beauty is what the Garden District life is about. The son-in-law, Quint (Barret O’Brien, my son, who played Bunky in Solitaire, the play, in Paris, and is now playing his father), has followed the path of greed and is pursuing pleasure through escape in the jaguar world of his wife (Kelly Lind, nominated in Madrid for Best Supporting Actress in a Short Film).

Rosary O’Neill and Rory Schmitt at work

Were any of the characters inspired by real people you know it heard about?

RO: These characters are so close to family members that in the original draft I actually used the real names of the relatives I was using, to get the rhythms the tone of the voice. I recall my sister calling Solitaire “the family play” and saying my parents would only accept the play if it made a million dollars. The lead, Irene, named after my glamorous and imperious grandmother, is actually a combination of the worst traits of my parents, both deceased. Versions of my family are there. I will say no more of the other characters to protect the living.

One of the characters just wants to be an artist and cannot bring himself to hold down an actual job, so what are some of the underpinnings behind his fragility?

RS: Rooster is an artist; he feels this calling deep in his bones. His mother refuses to accept this identity and wants to squash him into another role that is more suitable for her family. He is numb and cannot yet find the strength to leave the life that he knows and family that he loves.

RO: My brother was a philosopher who also wanted to be a magician. He was always doing hand tricks at table and infuriating my wealthy father, who couldn’t understand him. I got to see that artistic suppression in the lead son is a commonality in the beauty culture. My brother was like Walter Anderson, another famous Gulf Coast painter from Ocean Springs, Mississippi, who was an exquisite painter of wildlife. He would tie himself under pirogues to capture the perfect sketch. At home and around me in Louisiana and Mississippi were so many examples of genius artists who went array. Garden District exposes the punishment and glories of these lives, of men and women in the over-the-top beautiful Carnival World of hurricanes and masked balls.

A will and money are at the center of a lot of the drama here. Have arguments over wills led to problems in real families you’ve known?

RO: Of course! My Dad used to have weekly family meetings in which all adult children and their spouses (albeit reluctant) were called and required to attend to discuss inheritance and the distribution of money. Mostly the meetings were announcements from my father about what he planned to do. I was told as a young girl I couldn’t expect to inherit what my brothers did, and I shouldn’t rebuke the will. On the other hand, I’m grateful (as an artist) for what I did get, which allowed me to write for years for free. Being an artist was something the beauty and complexity of life in the South fed me to do.

Sherri Eakin as Jasmine Dubonnet in Garden District

Money problems also abound here. Why do you think a person born into wealth might end up in such a bad situation?

RS: Greed.

RO: Wealthy people use money to get love because they have to face dying and losing all that gorgeousness and service. When I was a child, my Dad was always redoing his will; he was thinking of ways to reduce taxes and promising this and that to various children. Even in his 90s, he had trusts and provisions and on and on. Even when he died, he had the best cemetery plot just a short walk from the chapel.

To that end, why do you think so many wealthy families—who don’t have the stresses of finances like lower-income or even middle-income people—have so many relationship problems?

RO: Wealthy people do have the stress of finances; they have bigger overheads, and they want more, and they expect to be served. And when things crash, it’s like immediately the Titanic. They are gambling with life big.

What’s your favorite thing about this film and your biggest hope for its future?

RS: Our favorite thing about this film is New Orleans talent, from the actors, to producers, director, writer, crew and editor. We want to show the world a glimpse into the life of New Orleans.

RO: Let’s bring work and art and beauty to all the talented artists of New Orleans. Let’s give artists hope by giving them work. Let’s rip back the façade of greed in these houses and expose the little bunny rabbits of people gloriously hopping about looking for space and love and beauty inside. Let’s preserve the legacy of Louisiana on film, her glorious Garden District, and her mystical people defying death with their sensuality, intelligence and gold coins. Let’s do give them words to speak from our 21st-century world and make it live now like Tennessee made it live in the 1970s. Let’s see who these people really are so they don’t give up, like Maggie says in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof: “Oh, you weak beautiful people who give up. What you need is for someone to hold on to you and love you, and I do, Brick. I do.”

Let’s love the weary gentle beauties of the Garden District in all their vile and guilty magnificence.

…

For more information about Solitaire and other titles by Rosary O’Neill, visit Concord Theatricals.

Header Image: Barret O’Brien as Quint Legere in Garden District

The Devil’s in the Details: Sharp Satire, Native Gardens and an Interview with Karen Zacarías

Newly Available for Licensing – January 2026 (UK)