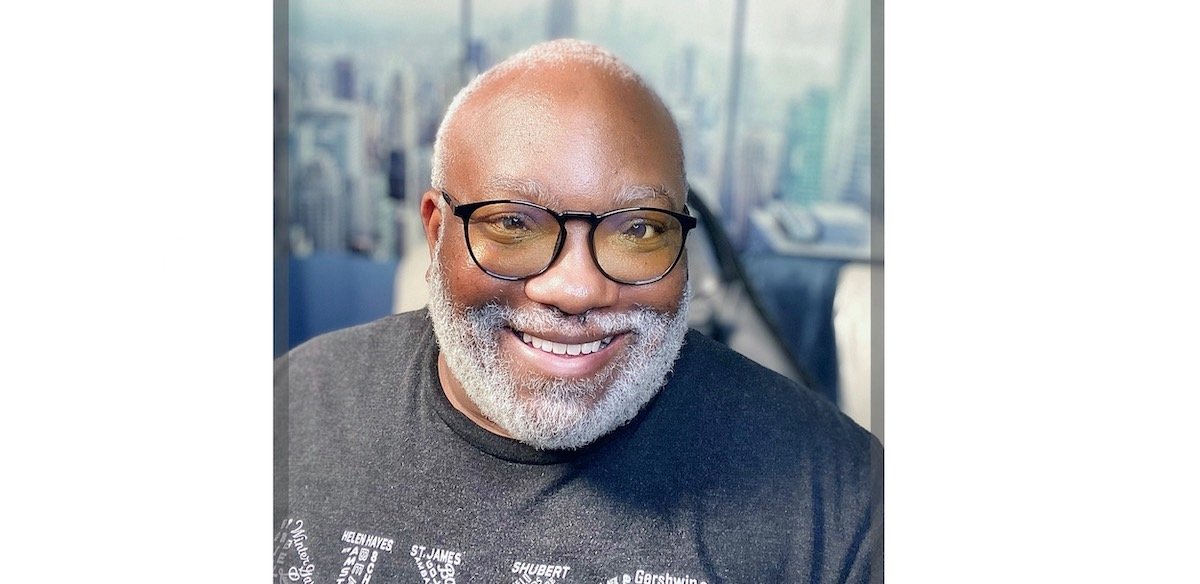

Corey Mitchell has made his mark as a phenomenally successful theatre educator, most notably at Northwest School of the Arts in Charlotte, North Carolina, where he has guided and directed thousands of students over the past two decades. The first recipient of the Tony for Excellence in Theater Education and the first recipient of the Stephen Schwartz Musical Theatre Teacher of the Year Award, Mitchell has risen to the top of his field. And now he’s launching a new venture: a nonprofit called Theatre Gap Initiative, aimed at helping students in their gap year, particularly students of color, to prepare for auditions for BFA programs.

We sat down with Corey to discuss his career, his philosophy towards theatre education and opportunity, and his newest venture. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

…

What made you first love theatre?

Well, ever since I was a little kid, I was always a cut-up, singing and dancing for family members and making up songs. I was also a sponge; just about every commercial that came on television I could almost sing back immediately, and my mother used to always ask me to sing the Pepsi song.

And I loved The Muppet Show, and whatever musical guests would be on The Love Boat, and the Dean Martin roasts. I loved those. It seemed so glamorous and fun, and people seemed so happy that I couldn’t resist what that felt like.

So, when did you first appear in live theatre yourself?

When I was a kindergartener! My first was doing a PTA assembly where I did a poem on stage:

I had a mule, his name was Jack.

I rode his tail to save his back.

His tail broke off and I fell back.

And I screamed, “Whoa, Jack!”

I fell to the ground, everybody laughed… and I was hooked! (Laughs)

And what kind of arts programming did you have as a kid?

It was Scouts, 4-H, taking dance and joining band (I played trumpet). I was also in chorus and drama and even formed a punk band with some friends in high school. My sister and I were both in the NC 4-H Performing Arts Troupe. That’s when I really discovered a life outside of my hometown. We performed all over the state and even took trips to DC. My mother used to sew costumes and would drive us to performances.

I did those things because I loved them… I didn’t know then what a triple threat, or a quadruple threat even was: to play an instrument and to sing and to dance and act. But that’s what was happening.

“Drama and band and choir… that’s why kids come to school and that’s why they engage. It’s for those things that feed their soul.”

So you were able to find an outlet for your artistic expression?

Yes. And it was amazing that we did, because Harmony, North Carolina, where I grew up, is so small, I doubt that you would find it on a map. Yet we had so many resources, and I was tremendously fortunate.

Honestly, the hardest part about being an educator today comes from the monetization of education and so-called “standardized learning.” It’s gotten out of hand and the things that hook kids in school, like drama and band and choir have decreased significantly. But, that’s why kids come to school and that’s why they engage… for the things that feed their soul and fuel their creativity.

How did you make the switch from performer to educator?

A scholarship called North Carolina Teaching Fellows. It paid for your college education and in exchange, fellows at a public school for four years.

I chose the University of North Carolina at Wilmington and said, “I want to teach theatre.” And they said, “Well, it just so happens we are planning to start a Theatre Ed program, and to have a student in place would be very helpful in getting this activated.” Well, the program never really got activated, so I ended up taking an extra year so I could get my degree in English.

In my first five years, I taught English and still I was involved with theatre. I performed, costumed shows and directed during that entire time but never lost sight of my desire to teach theatre exclusively.

“I was always thinking about ambitious and interesting challenges to take on in the theatre… doing things that had not been done before.”

And then you started at Northwest School of the Arts. What is unique about Northwest?

Northwest is this great microcosm of the entire city of Charlotte. The school system released a report a couple of years ago that showed most schools in our district are skewed predominantly black or white depending on its location in the county. Northwest is different because, as a magnet program, the criteria for admission is talent. Talent– NOT skin color and certainly not your pocketbook. Our specific population deals in talent, and as a result, the kids that go there reflect the diversity of the city.

I believe that misunderstanding comes from a lack of access to different people and cultures. When our kids sit together in class, collaborate with each other on shows and other projects at school, or just socialize in the cafeteria, they are breaking through those barriers that divide us. I make an extremely conscious effort to cast [in shows] a true reflection of the school and our community… I’m very, very proud of what that looks like. When I look at pictures that kids post on their social media pages they aren’t homogenized and that is really cool.

“I believe that misunderstanding comes from a lack of access to different people and cultures.”

You’ve done a number of Concord Theatricals shows at Northwest. Which ones do you remember most fondly?

Well, we’ve done Hair (US/UK), one of my favorite titles of all time. When I talked to the principal and I said, “I think next year I want to do Hair,” he said, “You’re not gonna do the nude scene, are you? People aren’t gonna be naked, are they?” And I was, like, “No!” And he said, “Well, all right, then.” (Laughs)

We did Purlie (US) and I’ve done For Colored Girls… (US/UK) and Anything Goes (US/UK) . We’ve mixed the traditional shows with a lot of the more avant-garde or cutting-edge shows.

What about material written when social norms and expectations were different?

For the things that have been socially acceptable because they were written by people from the dominant culture who’d say, “Well, can’t you just take a joke? This is what we find funny,” and dumb jokes that are at other people’s expense, I really try hard to flip it.

I teach musical theatre history, and one of my favorite artists within the canon is Bert Williams. Mr. Williams was a different kind of minstrel; he was a black man who did blackface and turned the jokes around on the other characters. For example, the trope of the lazy worker. Williams rearranged the joke and got other people working around him by pretending he didn’t understand the job. I’ve searched for those kinds of opportunities to “flip the switch” on people, if you will, when I’m doing shows that have some problematic tropes to them. We were working on Anything Goes! when the pandemic hit and addressing that problem with the two brothers.

I understand that art is a conversation. And art is not definitive. I understand that, and to a large extent, I try to do that. But where we really lose ourselves in this is to make the “otherism” the butt of a joke or the villain without any understanding or empathy.

So, I think a big part of where a lot of artists are coming from, especially artists of color, is to write us as a whole person. I don’t want to cancel, I don’t, but I do feel that if you are using my skin as a part of the story, then I want it to be an actual part of your story and not as a backdrop for it. I’ve been fortunate to direct a wealth of shows that do that, like All Shook Up, Purlie!, For Colored Girls…, In the Heights (US/UK) , Rent, The Color Purple and the list goes on.

“Art is a conversation. And art is not definitive.”

I’m so glad you included Purlie in that list. More people should know that musical.

Oh my gosh, I had the best time on that show. I did Purlie when I was in college and I played Reverend Purlie. I was literally just talking about Purlie in the meeting I that I came out of. Oh! By the way, put in A Chorus Line and how much I loved doing that show!

Will do! You had planned to take A Chorus Line to the International Thespians Festival in 2020, and you said you wanted it to be your swan song. Why did you choose A Chorus Line?

I think A Chorus Line (US/UK) speaks to so many aspects of what it is to be an artist and the love of performing and the love of theatre. “What I Did for Love” asks, “What would you do if you couldn’t dance anymore?” I really thought a lot about that. What if, in my next career, I do not have the opportunity to make art, to work with phenomenally talented kids and to help transition them into being responsible adults? What would I do?

That show! The level of difficulty, the technical level of difficulty, in its simplicity, like those three-sided panels in the back, those periaktoi – they just turn at key moments, but when they turn, it means something. When the light changes, it means something. Everything about that show has a deeper meaning than what is on the surface, and that’s why I think it was such a perfect swan song.

And by “level of technical difficulty,” I mean more than just the technical aspects of the show, as in “tech theatre.” I’m talking about the level of sophistication in the choreography, the communication that is happening on stage, the banter, and understanding when the characters are truly playing with each other, the tenacity, the triumphs, the pain, disappointments, when characters use things as a defense mechanism. All that gets laid bare and you see behind the masks. All of that speaks so deeply to the artistic process that I just love that show.

How did you adapt A Chorus Line when COVID hit and live performance and rehearsal were no longer an option?

Oh, it made me cry because I was so looking forward to it. We were so careful about that show in every decision and I couldn’t wait to show it. So, when the International Thespian Festival went virtual last year, we put together a virtual love letter. The students researched Michael Bennett, the original production staff, the cast and the show itself.

With that knowledge, the students were able to have conversations with several of the cast members from both the original and the revival cast of A Chorus Line: Donna McKechnie, Charlotte d’Amboise, Natalie Cortez, Baayork Lee, Ron Dennis, Deidre Goodwin. It was exciting, and I think for the students to have that kind of experience – as much as I absolutely hate that we could not take that show to Indiana to present, and I know they would have gone nuts over it – it was also very fulfilling and offered a much deeper understanding of the show.

“Theatre Gap Initiative is to help students in their gap year to prepare for auditions for BFA programs. But it’s also to start filling in some of those gaps that have become exacerbated over the years for students of color and students who come from economically challenged backgrounds.”

And now you’re launching the Theatre Gap Initiative, a nonprofit college-prep program for high school grads who aspire to apply for Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) and conservatory programs. Tell us more about TGI.

Theatre Gap Initiative’s programming is focused on helping students of color successfully navigate the process of applications, prescreens, and auditions.

It’s to help students in their gap year to prepare for auditions for BFA programs. But it’s also to start filling in some of those gaps that have become exacerbated over the years for students of color and students who come from economically challenged backgrounds, to help get them into the industry. Because we need all of those voices, we need those stories.

What inspired you to launch TGI?

On the Theatre Gap Initiative website, I’ve posted an essay called “Unsettled,” where I discuss this in detail. In a nutshell, after George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmad Aubrey and that bubbling over in the culture which led so many people to start examining the very industry that I’ve spent the last 20 years trying to escort students into, I started asking questions as well. Fortunately, I was able to engage in some profound dialogues last summer. One that had a lot of impact with me was a conversation I had with Colman Domingo and La Chanze and Sharon Washington. When I asked them, “Are you out in the streets?” Coleman’s response was, “I can use my knowledge, and use the tools that I have in front of me, to help make a change in the industry in a way that may not necessarily need me in the street. We need people out in the street protesting, but I feel I can use my tools in a different way.”

And that had me examining myself, of how I can use my own tools. Over the years I have seen how, more and more, the students who come from privilege are the ones who are able to go into theatre, and that bothered me.

That’s why I started the Theatre Gap Initiative.

How do you see TGI growing? What’s your hope for it in the long run?

My hope is that over the years I’m able to help transform how colleges look at students of color. So often, when a Black woman walks into an audition, if she doesn’t sound like Lillias White they think, “Well, she just a standard singer. Why do we need a Black girl?” I want to help other people see students in the way that they are as artists.

I also want to help those students in their isolation, because, particularly when it comes to musical theatre programs, they’re almost exclusively on predominantly white campuses. Howard University is the only HBCU that offers a BFA in musical theatre. The only one, singular.

In my experience as a classroom teacher, the number of kids that I’ve been able to help get into those programs, who come home to tell me about the microaggressions and the prejudices that they experience… I want to help be a bridge between those students and universities.

I want to franchise TGI so that everybody doesn’t have to come to Charlotte, so it does not feel like, you know, “coming to Mecca” to learn from me.

I want to normalize gap year programs, because particularly within the African American community, that is still something. When Black kids graduate, it’s basically three choices: it’s college or job or the military. A program like TGI can give students that extra year of preparation and be a real launchpad for them to succeed.

“To me, the way to a career for a student goes through a lighted path.”

And how can people support TGI? What would you tell them to do?

The first thing that I would tell them to do is give me airline tickets! One of the first ways to help even the playing field for students is to get them to those auditions. I will help prep the students, but I need people to help get me get them to those auditions.

The second thing is to help refer students to the program, because you know that expression, “If we build it, they will come.” Well, they will not come if they don’t know about it. So I’d really appreciate people helping: If you identify a kid that you feel could benefit, if you think, “Wow, that kid should be on stage, but they don’t know how to get there,” send them.

Because to me, the way to a career for a student goes through a lighted path. And quite often, kids come from schools where there haven’t been others who have lit the pathway for them.

Northwest is a unique place because we’ve had a number of students who’ve graduated from here who worked professionally. And there are all kinds of high schools around the country that have that have had students that helped to light the pathway. But it should not just be exclusive to these high school programs. There are kids who didn’t have those opportunities in high school that I want to help. TGI has assembled several luminaries within the business that are all desirous of helping to light that path –they are performers, professors, college students, arts advocates and allies.

“The role of an educator, and particularly the role of director, is to be a bulldozer – to clear the pathway for other people’s genius.”

You know, Corey, you have received so many accolades and honors, including the Tony and the Stephen Schwartz Award. So what’s your secret? What is it about your experience, your personality, or your philosophy that has led to such success for you?

Oh my goodness gracious. (Laughs) Well… I was once told that I am very charming and easy to talk with.

That is true.

I don’t know if that is true, but I do know that I try to relate to people. And I believe that the role of an educator, and particularly the role of director, is to be a lawnmower, and if a bigger piece of equipment needs to be brought in, to be a bush hauler, or if an even bigger piece, to become a tractor, or to become a bulldozer – to clear the pathway for other people’s genius. You know… working with a costume designer and talking and asking them some of the best questions I can possibly think of to help them, and then saying, “Okay, run with it. And how can I be of support?” And it works as well with students: to say, “I love, love, love your talent. Now, how do we amplify that and how do I make it easier for you to do that?” Those are the things that I really work at doing, with colleagues and with students.

Who was it, Vidal Sassoon, who said, “If you don’t look good, we don’t look good”? That’s really the thing that has happened: It feels like I’m bragging, but I feel like I have helped make so many people look good that it makes me look smarter than I am, better than what I am.

…

For more information about the Theatre Gap Initiative, visit www.theatregap.org.

For more information about A Chorus Line, Anything Goes, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Hair, In the Heights, Purlie and other Concord Theatricals shows, visit the Concord Theatricals website in the US or UK.

The Truth Behind… The Normal Heart

Musical Revues