Aleshea Harris’ What to Send Up When it Goes Down (US/UK) is a play, a ritual and a home-going celebration that bears witness to the physical and spiritual deaths of Black people as a result of racist violence. This summer, Brooklyn Academy of Music and Playwrights Horizons, in association with The Movement Theatre Company, presented the work at BAM for a limited run. The production returns this fall to Playwrights Horizons, where it will open on September 24.

As part of BAM’s educational programming, several high school students were invited to engage with the play through a six-week interactive workshop. Under the guidance of Ava Kinsey, Director of Education, and Mikal Amin Lee, Program Manager for the Education & Humanities Department, the students addressed and confronted the work, culminating in the creation of a personal critical response. Below, student Gabriella Officer-Narvasa recounts her transformational experience.

…

The Frames of Criticism: Theater Reviews and Racial Justice

For many New Yorkers, outdoor theater and other artistic performances are synonymous with warm summer evenings. Due to the pandemic, many of these usual haunts were either closed, rescheduled or limited to the public. When so many of us were concerned with staying safe and catching up on novels waiting to be read, it was a jolt of fresh air when the BAM Educational Department came to me with an idea. Although BAM is not an outdoor venue, the possibilities were endless, even for a mostly Zoom-based program:

For six weeks this summer, I had the opportunity to work closely with the BAM Educational Department to create a critical response and reinterpret Aleshea Harris’ play What to Send Up When It Goes Down. It was a singular experience that truly immersed me in the process of studying a play through multifaceted lenses.

The public has often viewed critics with suspicion, because oftentimes those critics have not adequately represented the communities on which their gaze has been focused. The field of professional criticism is dominated mostly by white males, and the work of creators of color is often viewed through the prejudices of white society. There is an inherent disconnect between the artist and the critics, a constant framing of these creations as belonging to the “other.” What to Send Up When It Goes Down is a play designed to give a safe space to Black audience members, a space for us to be free of this white gaze that invades every area of our lives. As a viewer and critic of the play, I was particularly struck by the de-emphasis on the white imagination and the white gaze. I was honored to have been invited to provide a critical response to such an important theatrical work.

The creation of our critical response was a unique process built on our own questions and curiosities about the play. Our final share was an amalgam of the many discussions and ideas that carried us through the weeks and the connections and parallels we drew between the play and our own experiences.

First, we read through the entire play aloud, trading parts back and forth and stretching our acting skills to their very limits. Most of our workshops were conducted over Zoom, and the time we took to explore the play through our own voices was integral to our ability to work as a creative unit in a virtual setting. In fact, I believe that it was those moments, often filled with levity or pensiveness, when the foundations of our final share were built. It was also then that we truly began to wrestle with the structural distinctiveness of Harris’ What to Send Up, a play that was also written to embody a pageant, a ritual and a homegoing celebration all at the same time. As we explored the play from start to finish, we often questioned which parts of the play coincided with each aspect of those embodiments.

During the program, we also worked on several WriteFreedom exercises. These were writing assignments meant to give my fellow student and me the chance to “remix” parts of the play that particularly intrigued us and piqued our interests. This was a chance for us to delve into the proverbial meat of the play and examine its meaning through our own writing and our own experiences. The WriteFreedom prompts gave us free creative rein to almost rewrite parts of the play in the image of our own lives. Instead of critiquing What to Send Up from a traditional standpoint, we extended the work through our own words. We approached our subject not merely as readers or reviewers, but as artists peeling apart the metaphorical onion of the play to draw forth the hidden layers that we wished to see. As Black artists, writers and creators, it was a particularly moving decision for us to explore a play like What to Send Up, a play that allowed us to engage with it on a deeply personal level, especially after the Black Lives Matter protests of last summer.

The aptly named WriteFreedom assignments gave me the chance to extend Aleshea Harris’ characters to encompass my own struggles with racial oppression. I wrote a monologue for the character Three, expressing the pain of the subtle sexism and racism I had experienced on my debate team and about my experiences at a Russian ballet school where I had to fight all the harder for every role I got. I wrote words for Seven, a character who was a victim of white violence, and I was inspired by articles I read in my history class, of the Sevens throughout the centuries (Harriet Tubman), the Sevens who had fought for America (Harlem Hellfighters, World War I battalion), and died at the hands of their own, the Sevens who had been children when their lives were stolen by state-sanctioned violence (Tamir Rice). I wrote about the protections of ancestors and the embodiments of my own ancestors, two sides of women facing colonialism on two different islands.

My WriteFreedom exercises were the sum of the things I have experienced and the things I have learned, of the knowledge of pain and the hankering for hope that I carry within me as a Black girl in America every day. And these writing exercises became a crucial foundation for our final presentation.

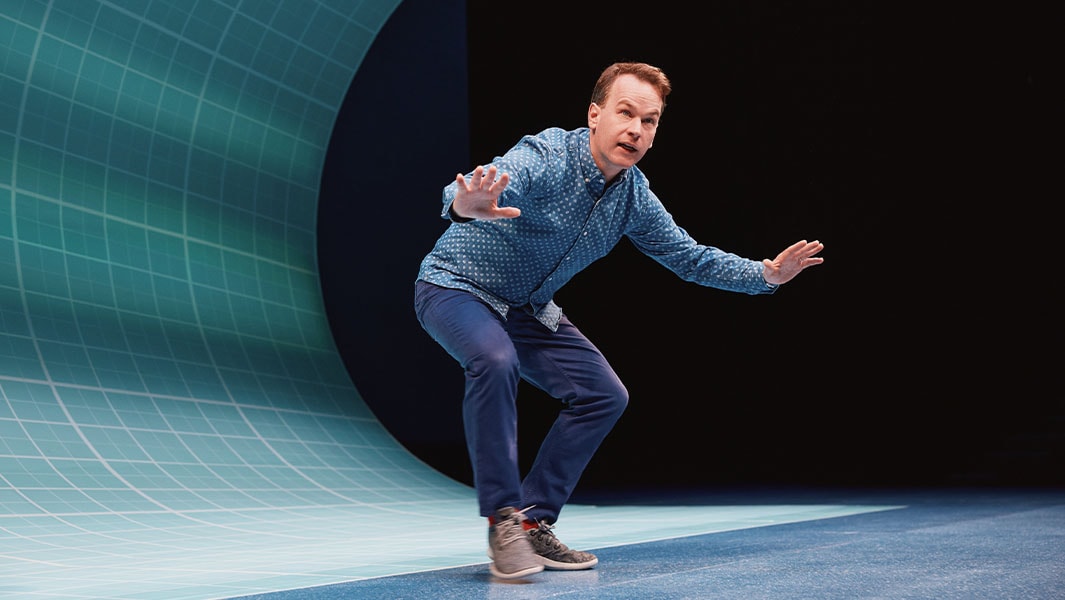

The most important part of creating this response, however, was seeing the live production of What to Send Up in person at the BAM Fisher Theater. My teachers and my fellow student and I walked into a space plastered with silkscreen images and photographs of America’s victims, of the Black men, women, and children whose lives were cut short because of the color of their skin. Seeing this space and pinning a black ribbon onto my dress was a sobering experience that truly allowed me to step into my role as a writer and a supporter after seeing this play performed live.

Until that point, our program had existed solely within virtual boundaries. We had perfected the art of Zoom inventiveness. We had a “living document,” a Google Document that became the receptacle for our writing exercises, for half-formed ideas we wanted each other to see, for pictures and videos and stories that related to the play and h

ow it connected to our own lives. We had only ever seen each other within the little Zoom squares on our respective cell phones or laptops, and we had only ever read the words of What to Send Up. But being in the space of the theater, listening to the songs and words of the talented actors as they brought all these characters to life, all the characters that had become so familiar to me over the course of reading the play.

It was a joyous shock to physically stand in a space with my teachers, my fellow students and the other audience members to participate in the rituals of the play that we had only read and speculated about, to bear witness to Aleshea Harris’ stunning work, which was not only an homage to the victims of white violence, but an homage to us as Black people living in a world and a society that tries to mold us like clay and shatter us like hardened pottery after we have gone through the kiln of injustice.

I am deeply grateful to the BAM Educational Department for such a unique experience that allowed me to engage on an emotional level with a deeply important play. Our “living document” lives on in cyberspace, and the black ribbon on my desk will always remind me to think about what I should be sending up when it all goes down.

…

For more information about What to Send Up When it Goes Down and other plays and musicals, visit Concord Theatricals in the US or UK.

Header Image: 2018 Movement Theater Company production of What to Send Up When it Goes Down (Ahron R. Foster)

Community Theatre: Consider These Plays & Musicals, 2025-26

Arthur Miller In Five Plays