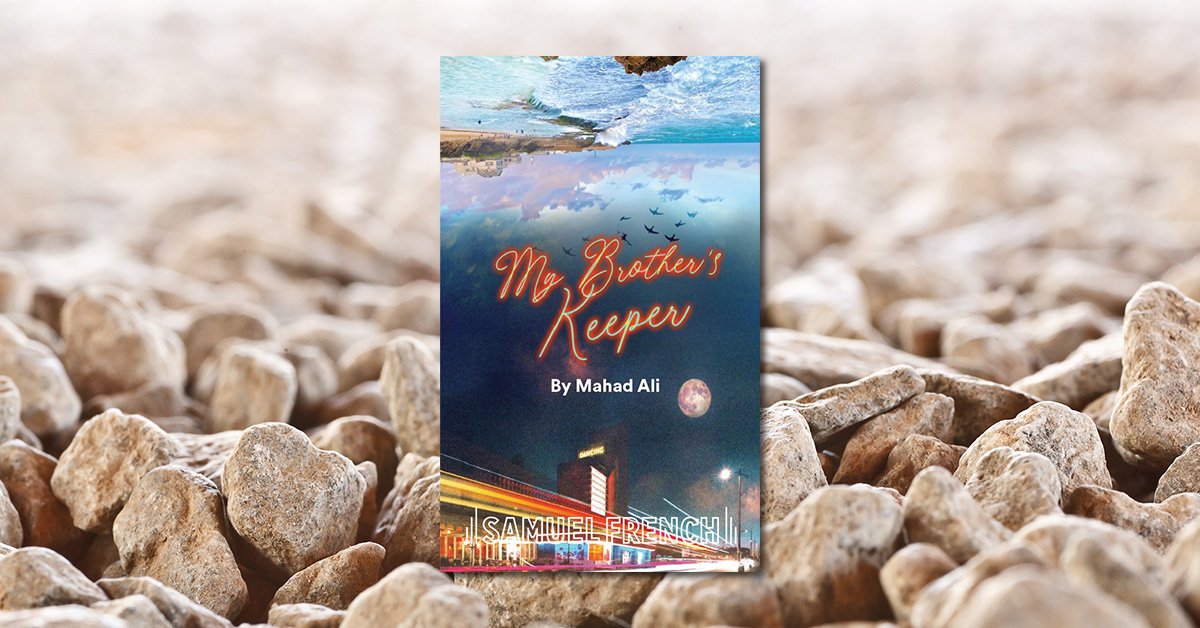

My Brother’s Keeper, playwright Mahad Ali’s debut play, explores the politics of immigration, religion and sexuality as a small British town tries to find its place at a time of great change in the world. Through two refugee brothers, Aman and Hassan, we discover a story of love, pain and learning to build community. We chatted with Mahad to find out more about the inspirations and the characters of the play.

…

What inspired you to create this story of two young immigrants arriving in a small British town?

I come from a background of Nigerian and Somali parents. I can remember in particular my Somali family members coming to Britain in the 1990’s during the civil war, it wasn’t an easy process but nowhere near hostile as it is today. So seeing what is happening now for refugees and migrants, I was inspired to try and break down the challenge of what it is like to settle in a new country and how the host community reacts to new faces joining it.

How did you navigate a balance between the hostility the brothers faced and the positivity they felt about living in a new country?

In one word – nuance. As people, we have moments of joy and moments of sadness, Hassan and Aman are no different. The reality is that the brothers enter a pretty hostile climate locally in a town that they are not welcomed in and the struggle of adapting to a country which is alien to them. However, they also develop friendships, relationships and have moments of joy which are unexpected. I think this is what the play is getting at, in that many areas of life we have good moments and bad ones. So as writers we shouldn’t shy away from the moments and show the nuance.

It’s scary to see the locals and politicians twist the truth to fit the narratives that they want to hear or believe. Tell us a little about the character of Linton, who has a strong belief in something that the rest of the characters do not hold.

Linton is a charismatic local, who has his finger on the pulse of the local community and knows how to tap into how they are feeling. He is part of the cult of personality, where someone with not much of a profile can build a following online and locally by “saying it as it is.” The contradiction in Linton is that he actually does care about his local community and we see that throughout the play. The question is whether he cares about the community or his own profile more. Which is a question we ask more and more of our political leaders.

Hotelier Bill does not understand his son Aidan’s mental health problems. Were there any difficulties in presenting the struggles of both sides on this issue?

Bill is a father of a certain generation who doesn’t talk too much about his feelings, which can in turn lead to a generation of sons learning to bottle up their emotions. In an era where Aidan’s generation are learning to open up and speak about mental health, something has to give. So the play tries to unfold through that relationship how an inability to communicate in such relationships can lead to more problems that are hard to come back from…

The scene at the beach with Aidan and Aman, and Aman’s romantic gesture toward Aidan, absolutely melted my heart. How important was it for you to develop the relationship between these two characters and explore their sexuality?

I think culturally it is a significant moment – Aman being African and being a Muslim, being in the west to unpack what he is going through. And how through his relationship with Aidan he is able to explore all of this. But also through that relationship to show what Aman brings to the table as a confident and daring young man, who pushes Aidan out of his comfort zone. It is a relationship with lots of twists and turns. But I want to present Aman’s character as a strong and independent-minded person, not a victim. Our Director, Robert Awosusi, has been brilliant in helping us to explore how we bring love, tenderness and joy into this relationship. I think audiences will see something really special.

Are there any other playwrights or theatremakers who have inspired your writing and the kind of work that you want to make?

I love work which speaks to the Black British experience such as Bola Agbaje, Roy Williams (UK) and Winsome Pinnock. It is distinctly British and Black as it’s a unique identity, which is now coming more to foreground. More further afield obviously the work of Wole Soyinka and August Wilson (US/UK). With an honourable mention of Arthur Miller (US/UK) whose work from studying it in school until now has stuck with me.

Do you have any advice for theatremakers looking to stage the play in future?

It’s a real ensemble piece. So if you are looking for a play in which five different characters, each of which have their own journey, and actors can really find themselves in this, it is a play for you. I think in exploring the text, get the actors to ask each other probing questions about community and what community means to them. Community is a big feature of the play, and the actors and crew you bring together in their own ways begin to form their own community.

What do you want audiences to take away from the show?

That community isn’t just those that look like us but everyone who lives within it, so we all need to be included if we are going to have any type of a civil society.

…

To buy a script of My Brother’s Keeper, visit the Concord Theatricals website in the UK.

Community Theatre: Consider These Plays & Musicals, 2025-26

Arthur Miller In Five Plays