Degas in New Orleans is a powerful play by Rosary O’Neill that delves into the life of famous painter, Edgar Degas, during the years he spent in New Orleans, Louisiana, after the Civil War. The play has been performed in America and France to rave reviews and Rosary recently came back from a trip to Paris where the work was read in French at Columbia University’s Global Centre and Amphi Turgot at the Sorbonne. Vincent Harmsen, the Coordinator and Stage Manager of the play, is a graduate student in American Studies at the Sorbonne. Below, he discussed his opinion of, and experiences with, the play with writer Megan Meehan.

Meagan Meehan: What was it about the life of Edgar Degas in New Orleans that most interested you?

Vincent Harmsen: I have to admit I knew little about Edgar Degas’ stay in New Orleans before I read Rosary’s play. Degas is mostly known in France for his paintings on Paris and the ballerinas of the Opera. That’s why her play was a striking new point of view on his life. The social part of his visit in New-Orleans particularly interested me. Rosary well expressed how Degas could have been shocked by the social way of life in Louisiana and the tensions inherent to the Reconstruction era in New Orleans. Degas did participate to the Commune revolution in Paris a few years before his trip, back in 1871. This revolution was all about equal rights between people and social equality. Imagining how Degas could have reacted to the white militias in New Orleans and the racial violence, he who was fed by this romantic and tragic view of the Commune, that is what thrilled me the most about his journey to New Orleans. Edgar Degas had this very romantic way of thinking, a scratched heart, that brought tension on every subject, love, art and politics. He was at the same time mannered and very touching, fascinating. I love to think that artists in that time were all full of passion and lyricism. It is also what we can feel in his paintings, the intensity of colors, the strength of people’s emotions.

Meagan: Which of his New Orleans paintings appeals most to you?

Vincent: Well to follow what I said, I enjoy “A Cotton Office in New Orleans.” Every character in the scene is captured inside his own activity as if the world would collapse without disturbing him at all. Degas recreates a society from the past. I see phlegm in how the characters behave, social status in the clothes and the hats and in the center of the painting, as the cornerstone of all this society, the cotton. It is an incredibly well thought-out painting. In this painting, I like to dive myself not into the entire scene but into just one character or one motion and then go from one side of the painting to the next and it is already a complete story which Degas whispers to me.

Meagan: Is Degas well known in France?

Vincent: At each step of my work as coordinator of the play, Degas in New Orleans, in Paris when I had to meet different people in scholarly administration, in the cultural institutions or among my friends not one single person didn’t know who Edgar Degas was. Not only is he well known in France but he stands as a highly appreciated painter. As I said, everybody knows his famous paintings of the Ballet dancers. People usually know him as one of the very remarkable impressionist painters. His paintings stand side by side with famous painters such as Monet and Renoir. Edgar Degas has been in fact one of the key factors that attracted Parisians into Rosary’s project. I just had to tell them the play was about him and their eyes shined.

Meagan: Who in Edgar’s New Orleans family interests you the most? Why?

Vincent: There are two ways I relate to a character. I feel for a very naive character, usually a child, or to a completely dubious one. In this play my empathy would either turn to Jo Balfour, the ten years old stepchild of Edgar’s brother, for her kindness and innocence, or to his uncle, Michel Musson, this ironic man who doesn’t fit in any frame, who is quite fascinating.

Meagan: How was Edgar’s family in New Orleans like or unlike a French family?

Vincent: I guess it is quite simple. What made Edgar’s family so original was that they were a perfect mix of French and American behavior. The children were raised in this love of art and classics which was so specific to the French bourgeoisie. Alternatively, the social and political environment, of racial tension and economic struggles undoubtedly impacted them. But that appears to be the case with many immigrated families who try to maintain both French and American identities.

Meagan: Why do you think Edgar never went back to New Orleans?

Vincent: Well, it seems to me Edgar was on this journey both fixing and closing a painful chapter of his life. We usually believe artists live their art alone and restrain their social activities in order to focus themselves on another plan, the one of art. Degas tells us in Rosary’s play that his painting is broken because he is obsessed with his love for his sister-in-law, (I hope I am not spoiling it for those who don’t know the play yet). His trip to New Orleans was his own way of ending this love and his bounds to his family so he can once again paint as he painted before.

Meagan: Were Edgar’s life circumstances similar to those of other artists in the 1870s?

Vincent: Sadly, I am not specialized in the history of art so I am afraid I am not able to answer this question. Even so it seems quite unusual for a French artist to visit the United-States back then. However, I believe that the same passion lived in all those artists at the end of the century in France, a passion that drove them into all kinds of fervent endeavors without making no difference between public and private life. They placed art on the same level of intensity as politics or love. Victor Hugo said that “every man stands in the night seeking for his light”, I think his words reveal the kind of passion artists had in their guts in 1870.

Meagan: Has much changed for artists in Paris in the 100 years since Edgar’s death?

Vincent: Yes and no. Of course, the economic and social status of artists has deeply changed since Edgar’s death. France respects art nowadays more than before. Artists have an official status that allows them to live from their art even if they can’t reach a sufficient public to earn their life. In France it is called the “Status of Intermittent”, it states in the law that in cultural fields, one can work periodically for multiple companies. He will then report his hours to the state and leave contributions according to what he earned. This will basically allow him to be granted allocations, according to the amount of hours worked, when he is unemployed. French believe that art works like a wheel, sometimes you stand at the top, and you earn alot, and sometimes you stand at the bottom because your project failed to reach its public. What hasn’t change though is this incredible love for art in France. From the poorest to the richest, everybody enjoys art. You can see in the streets of Paris homeless people who are reading authors like Maupassant or Baudelaire. It is amazing, I can’t even believe it. Our country is facing a major economic crisis, and the cinemas, the concerts, and the festivals have never been so full!

Meagan: How did you meet Rosary O’Neill?

Vincent: I met Rosary in September in Paris when she was hosted by the Irish cultural center of Paris. My graduate professor, Annick Foucrier brought me to have a conversation with Rosary about art in the US and the French and American ways of thinking about art. I was so thrilled to meet R

osary, I worked in the theatre for eleven years before I moved to Paris, so I confessed to her I was in need of a drama project. This is how I eventually became the coordinator and stage manager, of the readings of “Degas in New Orleans” at the Sorbonne and Columbia Universities.

Meagan: What are your plans for her play in Paris?

Vincent: The project includes Ada Denise, inspiration for the project, professor Joseph Danan, French professor in theater at the university Sorbonne-Nouvelle Paris 3, and his graduate students in master of theater studies. They will read the play at Reid Hall, the Columbia Global Center of Paris (thanks to Brunhilde Biebuyck, Administrative Director) and at the amphitheater Turgot in the Sorbonne University (thanks to Annick Foucrier, Chair Department of American Studies.) The idea is to have students and people in general discover American theater, which is I think too little known. The readings will be enriched with some music and pictures of Degas’ paintings but it will be kept as simple as possible in order to promote Rosary’s text.

Meagan: Where are you hoping to have this play performed afterwards?

Vincent: A great question to which I yet don’t have the answer. We will film the event in order to attract actors or directors. Paris is so full of plays and theater that it is nearly impossible to direct a new one. I think it might be possible to stage the play with local directors outside of Paris or with theater students who are more opened to hardy projects, but this is another story.

Meagan: What else would you like to mention?

Vincent: I am very proud to support this project and to help Rosary. When I was young my family used to welcome foreign students in our home, especially Americans. There I learned the need to have strong relationships between France and the US. There are never enough cultural ties between our two countries and we have to bear in mind that what was already achieved can easily be undone.

Meagan: What is the most difficult thing about doing a reading of a new play in France today?

Vincent: What comes directly in my mind is reaching and keeping the links between all the people involved in the project. But isn’t that exactly why I am here (as coordinator of the project) to do it?

Meagan: What are you so happy about doing this project?

Vincent: Except from all I said above? Rosary’s enthusiasm and energy! She is a real “atomic battery!” That’s a French expression to point out in a very positive manner that one is extremely enthusiastic and willing. In French, we say of someone who is tired or a bit slow that she is “on a low battery.” And in reverse, when someone is very enthusiastic we say that “she is a real atomic battery.” Atomic batteries are used for example in submarines in order to have them move with a more powerful energy. I guess it is typical French. Nuclear may not be as well considered in the US as it is in France. Nuclear in France is sacred, really. Her excitement and passion are truly powerful!

To purchase a copy of Degas in New Orleans click here, and to learn more about licensing a production, click here.

Community Theatre: Consider These Plays & Musicals, 2025-26

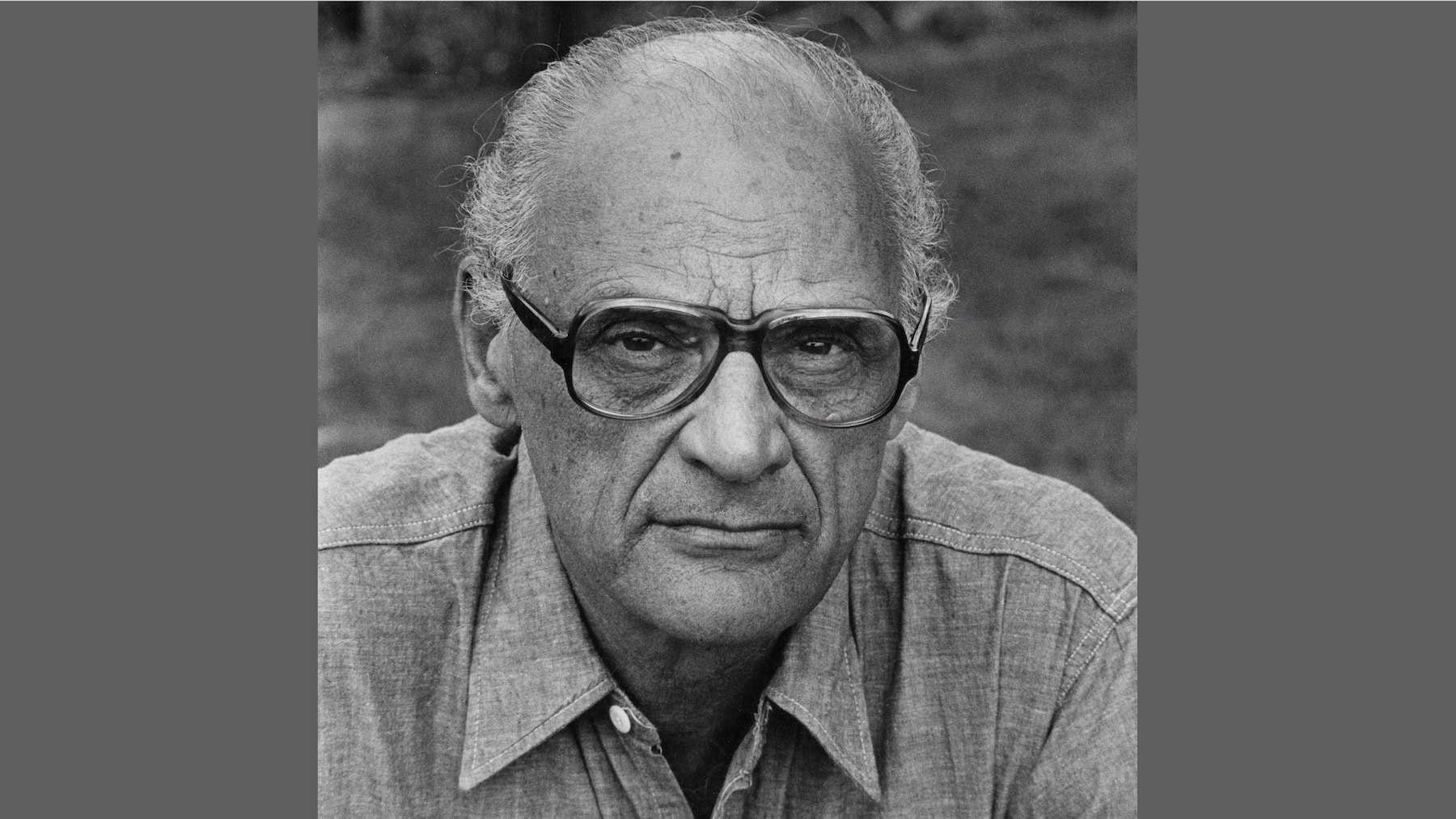

Arthur Miller In Five Plays