For decades, Tams-Witmark published a periodical newsletter called Musical Show. The mini-magazine (originally a mini-newspaper) included photos and summaries of Tams shows, along with essays, interviews and reminiscences from some of Broadway’s greatest writers. We thought it would be fun to revisit some of those articles, so we’ll share those gems here from time to time.

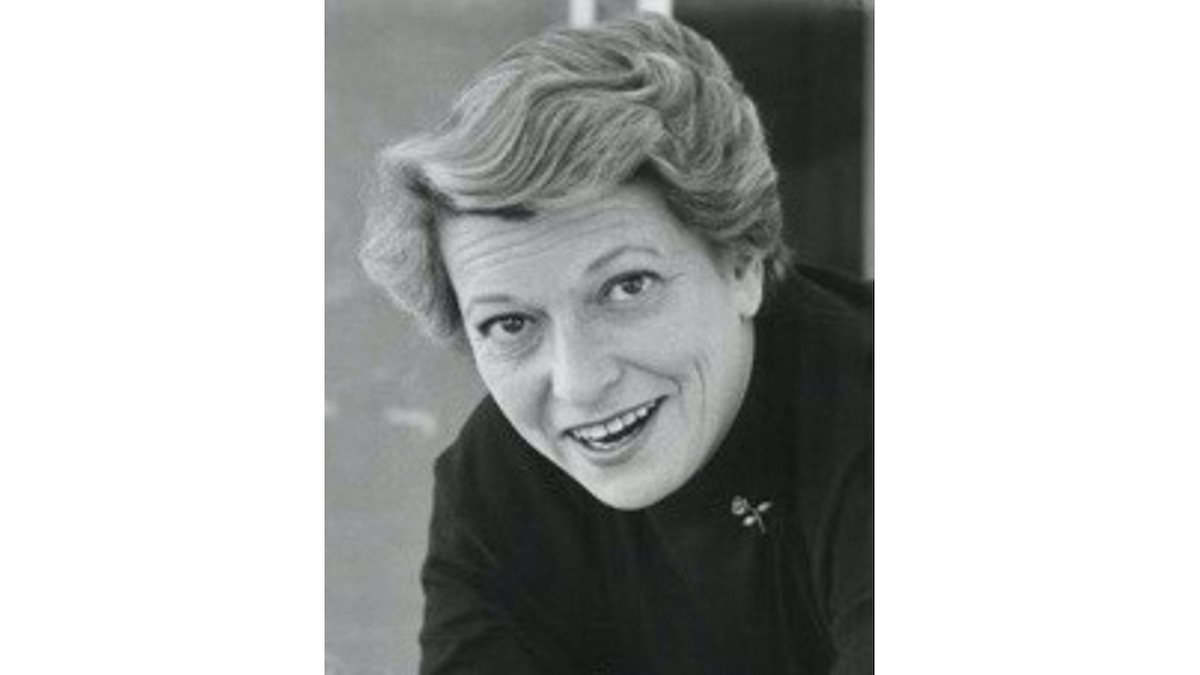

Here’s an essay from Isobel Lennart, the bookwriter for the 1964 smash hit Funny Girl. First published in October 1966, this comical look back on the creative process earns Ms. Lennart the title of “Funny Girl” herself.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Lennart became a successful Hollywood screenwriter, penning hits like Love Me or Leave Me, Please Don’t Eat the Daisies and Two for the Seesaw. After writing the book for the stage version of Funny Girl, Ms. Lennart wrote the screen adaptation, earning a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Screenplay.

FUNNY GIRL: “The Most Horrible Experience Of My Life”

By Isobel Lennart

October 1966

The morning after Funny Girl opened on Broadway, I left New York and came back to nice, quiet, sensible Hollywood, where I have lived and worked most of my adult life. Well, “left” isn’t quite the word. I fled – screaming. Well, “screaming” isn’t quite the word, either. After a couple of months in rehearsal with Funny Girl, and another three or four months on the road with it, I didn’t have enough strength to scream. I moaned – that’s what I did. And that’s what I kept doing for almost two years.

It was the most horrible experience of my life, I told anyone who would listen. Writing the libretto for a musical (this was my first) is the best way to lose your sanity, your judgment and your teeth. (I lost one, so I should know.)

Now, everyone in the theatre acknowledges that getting a musical on is The Worst. And most people on Broadway agreed, at the time, that Funny Girl, from the day it went into rehearsal, was The Worst Worst – in terms of turmoil, misery, and general horror.

All musicals, according to the press and gossips, are in trouble someplace – either in Boston, Philadelphia or New York – during preview week. The word went out on us – every day, in every booth at Sardi’s – that we were in trouble in Boston and Philadelphia and New York during preview week. It’s true that we played sold out at every performance, though shows in theatres around us were papering [distributing free tickets to fill otherwise empty houses], but we had Second Act Trouble. Every cab driver in every one of those cities knew it, and told every passenger – including me.

Once, in Philadelphia, during the interval, Jule Styne heard a lovely old lady say to her husband (or perhaps it was her lover), “I love the first act, but I don’t think much of the second.” He said, understandably enough, “But you haven’t seen the second act yet.” “That’s all right,” she said. “I’ve heard.”

Everyone heard – until we opened. Then it didn’t matter.

What made it such a nightmare, if we were doing so well from the beginning? Well, the fact that Jule Styne, who wrote the music, and Bob, who wrote the lyrics, and I, who wrote the book, and Jerome Robbins, who supervised the production, and Ray Stark, who produced it, all wanted it to be better. We got it better, too – but we all aged considerably in the process.

My own grief came largely from my inexperience. After years of writing for the screen, I can usually tell if what I’m doing is good or no good. In the theatre, with no backlog of experience to give me confidence in my own judgment, I had to listen to everyone. And if you listen to everybody for long enough, you turn into a sponge – absorbing the worst of everyone’s advice, losing even the pretense of conviction of your own. I was particularly thrown by what – I was told – is the enormous difference between writing for the screen and writing for the theatre. It is different, but not all that different, once you latch onto it. (Which I did only about a day before we opened.)

I had difficulty understanding live audiences, too. I’m still baffled by them. For example: in Philadelphia I wrote a scene that was an absolute smash on a Tuesday night. You never heard so many laughs. It laid an egg Wednesday night. I wrote a new scene for Thursday night. Smash. Friday, egg. And so it went. I wrote seven separate scenes and only the seventh got laughs more than one night. Why? I don’t know to this day – but it’s the sort of thing that prevents you from getting bored when you do a musical.

Funny Girl continued to have problems in the press even after it opened and was a tremendous hit. Barbra Streisand was so magical in the part that the columnists assured us no one else could play it. Well, when Barbra’s contract with the show came to an end, Mimi Hines took over for her. That was almost a year ago, and – the last I heard – it was still running. The National Company engaged Marilyn Michaels, and that’s been playing sold out for a year and has a year of bookings ahead of it. I understand that when Marilyn misses a performance, the audience is wild about her understudy, Sandra O’Neill. There’s a girl playing it in Australia who’s become the toast of the town there – any town she plays in.

I stayed away from Funny Girl for a long time – I thought it would be too painful an experience. But a few weeks ago, in Los Angeles, I went to see it. At the risk of seeming immodest, I must tell you that the audience loved the show, and so did I. I loved Jule Styne’s music, I was wild about Bob Merrill’s lyrics, and I even liked some of my own work.

I hope you will, too.

…

For more information about licensing a production of Funny Girl, visit Concord Theatricals in the US or UK.

UK School Musicals – Let’s Travel

The Devil’s in the Details: Sharp Satire, Native Gardens and an Interview with Karen Zacarías